Heat stress is one of the most important causes of economic losses for companies within the poultry sector in tropical climates. Causing significant impacts on productivity and mortality.

Under normal environmental conditions, birds are capable of maintaining their balance with the environment. However, when temperature fluctuations occur, birds must compensate for these variations above or below their thermal comfort zone.

Heat stress begins when the ambient temperature rises from 26.7 ° C and becomes potentiated with temperatures above 29.4 ° C.

When birds begin to pant, physiological changes within their bodies have already become activated in order to dissipate excess heat. Hence, any action or strategy that can be adopted to help birds stay comfortable before reaching this point, will contribute to maintaining:

- growth,

- hatchability,

- egg size,

- shell quality,

- and peak production conditions.

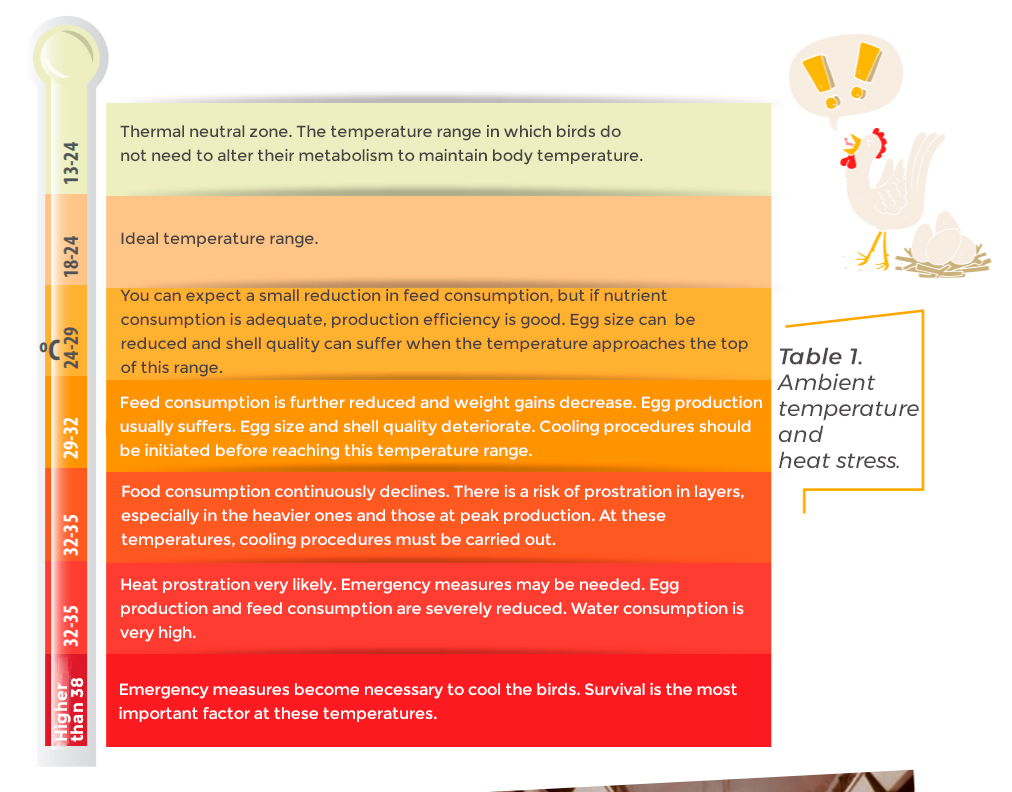

Table 1. Physiological changes and events that occur as the environmental temperature varies.

Birds are very sensitive to heat outbreaks, and cannot endure extreme temperatures for long. This is due to the fact that they lack sweat glands, which does not enable them to dissipate heat through sweat. Additionally, their feather cover, makes it difficult to dissipate heat that is generated inside their body as well as heat from external sources.

Layers can suffer more than other birds, since most of the facilities on today’s farms are automatic or generally housed in cages.

Chickens in cages are totally dependent on the proper functioning of ventilation equipment to dissipate heat from their bodies.

With genetic changes, and types of facilities and cages, chickens have lost resistance to extreme heat.

As the bird’s body temperature increases, feed consumption, growth, feeding efficiency, viability, and quality of the eggshell decrease. This is particularly severe when the ambient temperature rises extremely, since the possibility of losing heat through non-evaporative means (loss of heat through the skin) is significantly reduced.

Adult birds are capable of resisting cold much better than heat. As their internal temperature may drop to 23.9 ° C without causing mortality. The combination of heat and humidity can be deadly; this sum must not exceed 106.7 when expressed in °C.

For example, when the temperature is 26.7 ° C, and the RH is 80%, or 26.7 + 80 = 106.7, heat stress begins. It is very important to know how to manage these factors, i.e: when there is a lot of humidity in tropical areas:

- At midnight: More ventilation must be provided. While wet walls, humidifiers and sprinklers must be avoided.

- At noon: When there is less humidity and more heat, ventilation should be used as much as possible combined with sprinklers, humidifiers and wet walls.

When birds are exposed to high temperatures, body heat is increased by the combination of high external temperatures and the energy associated with activating metabolic processes required to dissipate body heat. This heat dissipation is increased by the position the bird must adopt to increase its vascular surface area by vasodilation. Causing an increase in water consumption and an acceleration in the respiratory rate. This respiratory acceleration is particularly important for birds as water evaporation becomes a means of heat dissipation. Unfortunately, this evaporative cooling only achieves a small reduction in body heat.

The birds’ comfort zone decreases as they age and grow.

Heavier breeds tend to have more problems with heat stress since they have less surface area to dissipate heat per unit weight. Another variable that influences susceptibility to heat stress is the birds’ previous exposure to this type of stress.

In warm months, temperatures can rise to 35 ° C and 38 ° C it is critical that birds dissipate body heat into the environment. As it was previously mentioned, birds don’t sweat, so they must dissipate heat in other ways to keep their body temperature around 40 ° C to 41 ° C. Body heat is dissipated into the environment through radiation, conduction, convection and evaporation (see Table 2) .

The first three routes are considered as sensible heat loss. These methods are effective when the ambient temperature is below or within the birds’ thermal neutral zone (13 ° C to 24 ° C) (see Table 1). The proportion of heat lost through radiation, conduction and convection depends on the difference in temperatures between the bird and the environment.

Birds lose temperature on surfaces such as legs and feathered areas under the wings.

The purpose of ventilation in poultry houses is to maintain sufficiently high air velocity or low enough temperatures within the house, for birds to maintain their body temperature through sensible heat loss methods. (see Table 2)

Once the environmental temperature reaches 25 ° C, heat loss methods begin to change from sensible (radiation, conduction or convection) to evaporation or latent.

The dissipation of body heat through evaporation requires energy expenditure from panting (hyperventilation), which begins to occur at an approximate temperature of 26.5 ° C. Gasping refers to rapid breathing with an open mouth in an attempt to cool down through evaporation. This is a normal reaction in birds attempting to withstand and survive heat stress.

Chickens in their normal state and in a thermo-neutral environment, breathe 25 times per minute. However, when temperature surpass their limit , this rate can rise to 250 times per minute, and the birds may eventually perish.

Panting removes heat through the evaporation of water from moisture in the respiratory tract. However, this mechanism also generates body heat and produces water loss in the bird’s body.

Layers affected by heat stress lay very thin shell eggs. This is related to the acid-base imbalance that occurs within the blood due to the onset of gasping(hyperventilation).

As birds gasp, they lose excess CO2 gas from their lungs. It is important to understand that due to hyperventilation and panting, layers lose a large amount of bicarbonate ions (HCO3)-1 that should be part of the eggshell as calcium carbonate crystals. For such reason, it is recommended to replace at least 30% of added salt with sodium bicarbonate or at least to add supplements containing bicarbonate ions in the drinking water in order to improve the bird’s electrolytic balance.

When CO2 blood concentration drops, it causes a rise in blood pH, making it more alkaline. As blood pH rises, the the amount of ionic calcium (Ca+2) in the blood decreases.

Ionic calcium is the calcium used by the gland that produces the eggshell. Even if the amount of calcium in the diet is increased, this problem cannot be corrected.

When feed consumption decreases due to heat stress, calcium and phosphorus intake also decrease, contributing to the production of fragile shells.

As the pH of body fluids changes, feed consumption becomes more depressed causing an adverse effect on the bird’s growth, production and overall performance.

Usually, the heaviest and largest birds with the best body conformation are those that die, since they have excellent production rates and higher weight which causes more stress. Most of the birds that suffer from heat strokes die at night. Meaning that birds suffer during the day, as they are incapable of dissipating the heat. Hence, they absorb all this heat like sponges during the day, which eventually leads to their death at night.

The effects of heat stroke or heat stress can be mitigated through the application of a comprehensive plan that contributes to improving birds’ conditions. Allowing them to better deal with this stress scenario.

This strategy should include:

- A complete biosecurity plan

- A management plan for ventilation and water management in terms of quality and temperature

- An adequate diet and nutrition plan

The availability, quality and temperature of water is very important.

The only way in which hens can maintain their high production rates under hot weather, is by facilitating body heat dissipation while still receiving their daily nutritional requirements during the cooler hours of the day, when it is easier for them to lose extra calories through digestion. This can be done by applying temporary fasting, as eating in the hottest hours of the day can be deadly. Digesting feed during these times generates heat, further aggravating the situation for the birds. Therefore, feeders should be empty 1-2 hours prior to the onset of heat and 1 hour after. This feed removal can be supplemented with a midnight feeding plan which can help maintain production in hens regardless of their age, as it does not interfere with their sexual maturity. This strategy also improves egg quality and shell color.

Supplementation with multivitamins, electrolytes and individually titrated vitamin C solutions in water is also used.

There are countless practices that have been used for years with good results, such as:

- Improving bird density during the critical stage

- Use of cold or summer diets, which include added fat levels of up to 4.5%

- Concentration of diets in the use of synthetic amino acids and inclusion of higher levels of Calcium and Phosphorus to prevent cage fatigue