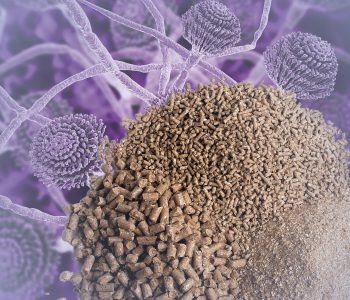

Prevalent Mycotoxins in Grains and Their Impact on Swine::

Aflatoxins

While acute aflatoxicosis is infrequent in pigs, it leads to significant liver impairment, manifesting in symptoms like bleeding, jaundice, and sudden death.

Vomitoxin

It disrupts protein synthesis, influences immune modulation, and impacts neurotransmitter activity in the brain.

Zearalenone

Produced by Fusarium graminearum usually before harvest. Structurally mimics estrogen, affecting the reproductive tract in pigs.

During lactation, zearalenone passes through milk, inducing vulvar swelling and redness in newborn female piglets. In boars, zearalenone suppresses testosterone levels, sperm production, and libido, especially in younger animals.

Fumonisins

Generally cause immunosuppression. Acute toxicity leads to a condition called porcine pulmonary edema, characteristic of fumonisin poisoning, causing heart failure and fluid accumulation in the lungs.

Pigs with acute toxicity exhibit severe respiratory signs, difficulty breathing, cyanosis, and death.

Ochratoxin

In cases of ochratoxin A toxicity, pigs often have slow growth and poor feed efficiency due to impaired kidney and liver functions.

Feed intake is usually unaffected. In some cases, the only toxicity effect of ochratoxin A is detected at slaughter due to the appearance of pale, firm, and enlarged kidneys.

CLASSIFICATION

The subsequent category of mycotoxins is non-polar. As they lack an electrical charge, clay-based binders prove ineffective. Yeast cell walls, on the other hand, excel in preventing the impact of these mycotoxins.

Mechanisms of Action of Non-Polar Adsorbents:

- Adsorption: Yeast cell walls, negatively charged due to carboxyl, phosphate, and amino groups, attract mycotoxins, usually positively or negatively charged, through electrostatic attraction. This adsorption process helps retain mycotoxins, reducing their availability.

- Ion exchange: Some mycotoxins can interact with ions present in yeast cell walls through an ion exchange process. For instance, certain positively charged mycotoxins can bind to carboxyl or amino groups in yeast cell walls, contributing to their elimination or reduced bioavailability.

- Chemical bonds: Yeast cell walls contain functional groups like hydroxyls and aminos that can form bonds with mycotoxins. These bonds can be covalent or non-covalent, resulting in mycotoxin retention.

- Biochemical processes: Some yeasts produce enzymes that can degrade or modify mycotoxins in contaminated foods or feeds. These biochemical processes help deactivate mycotoxins, reducing their toxicity.

It’s crucial to note that the effectiveness of yeast cell walls as mycotoxin adsorbents may vary depending on the specific composition of mycotoxins and yeasts used.

In vivo, appropriate conditions must be provided for mycotoxin and the binder to adhere or form the binder/mycotoxin complex. A diet should promote physiological elements for this binding to occur.

When formulating a pig diet, factors such as intestinal movements, gastric emptying, pH variability, and intestinal transit speed should be considered.

An essential aspect to consider is the absorption and desorption capacity of a binder. Desorption is the binder’s ability to release a percentage of absorbed mycotoxin. A poorly modulated gastrointestinal system can affect the desorption capacity of the binder, releasing mycotoxins.

Another critical aspect when dealing with mycotoxins is to prevent their production during storage. If adequate contingency measures are not in place during this period, the increase in mycotoxins in the silo can be significant and challenging to control.

It should not be forgotten that Latin American countries have favorable conditions (humidity and temperature) for fungal proliferation in stored grains.

Points to Consider During Storage:

Moisture monitoring:

Monitor moisture by season (winter, summer, or cold season). This measurement is crucial because if we turn on the ventilator, and the humidity is high, we are not ventilating the grain but introducing more humidity inside. Therefore, we must identify the time of day when relative humidity is lowest.

Grain temperature:

Identify the grain temperature during the day or night and the season (winter or summer). We aim to inject air into the silo to lower the temperature. It should not be forgotten that a seed is an embryo, and it reacts to the environmental conditions it faces.

Water condensation:

This is a crucial point in cases where the environmental temperature is higher than the interior temperature of the silo. This has an effect on the roof sheet or the silo walls. This clash of temperatures, coupled with the presence of humidity, leads to the condensation of water within the silo structure.

Once this moisture is condensed, the roof and walls will drip water onto the stored grain. It is essential to identify the time of the year when this effect intensifies.

Image 2: Worker overseeing the cleaning and water condensation control before corn enters a silo.

One of the most effective measures for preventing fungal growth during storage is the application of organic acids to the grain as it enters the facility. Acidity efficiently prevents the proliferation of fungi.

Conclusions

|

You also like to read: “Mycotoxin levels in soybean meals”