17 Apr 2023

17 Apr 2023

As the final entry of this section dedicated to calf nutrition and weaning practices, we will talk about the breeding cow.

Besides the technical aspects which have been previously discussed, economic factors associated with these production practices must also be considered.

As we are talking about rapid development of calves, which are destined for fattening. Which is in the interest of two types of farmer profiles:

For those who carry out the full cycle within their production system, this is positive because it shortens the process and leads to animals with enhanced potential for weight gain.

For those who carry out the full cycle within their production system, this is positive because it shortens the process and leads to animals with enhanced potential for weight gain.

This practice is also important for those producers that sell calves to other farmers who carry out the fattening phase. Hence, it interests both parties. Those who sell, accelerate and anticipate their next batches. While those who purchase, acquire animals with better profit potential, as these already consume solid diets and their adaptation to feeders will be much faster.

What about the cow?

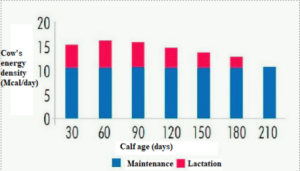

These early weaning practices, always tend to be advantageous for the cow. According to the NRC (1996), the cow uses an important portion of its energy reserves during the whole lactation period with the calf by its side. This occurs up until the calf is 180 days old and i then starts to decrease. (graph 1).

Figure 1. Energy demands during lactation (NRC, 1996)

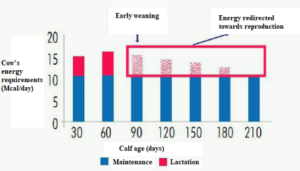

Despite this fact, cows can be helped with weaning techniques. Allowing to redirect the energy demands of calves to benefit the cow (figure 2).

Figure 2. Fraction of energy redirected to the cow with through the use of early weaning (NRC, 1996).

Gomes et al. (1986), Molleta & Perotto (1997), Restle & Vaz (2001) assessed weaning in cattle in different periods of the productive cycle, but during the same time of year. Through this evaluation, they found significant differences regarding the mean weight of cows.

![]()

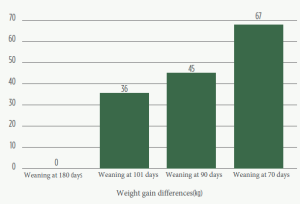

Figure 3 shows the average weight of cows during different weaning periods, considering that all calves reached 180 days of age.

Cows whose calves were weaned at 70 days of age, had 67 kg more body weight on average compared to those cows in the control group.

This faster recovery of body condition translates into a better utilization of nutrients by the cow.

Figure 3. Average obtained through the assessment of weight differences in cows with different lactation periods with the calf at foot. Gomes et al. (1986), Molleta & Perotto (1997), Restle & Vaz (2001)

| When cows are not not lactating and they start re-gaining weight, their metabolic demands are at a minimum. Allowing them to be ready to start a new reproductive cycle. This can be achieved earlier than it would conventionally occur with these types of weaning practices. |

Herd healthcare

We have mentioned management and nutrition practices, but we cannot forget about herd health as a key factor for success. It is also very important for the herd vaccination plan to be fully met.

Whether they are precocious or not, calves will suffer some stress. Therefore, the application of vaccines or other medical treatments during weaning, will not elicit the desired response.

![]()

An alternative for reducing the challenge posed upon calves, is to schedule vaccination for a few days before weaning. With the application of a booster later on. That way, we reduce the challenges to which the calf’s immune system is exposed to during these days of higher stress.

This practice takes animal welfare into account, making it fundamental and necessary for the success of any productive system. Herd health plans must consider Clostridiosis and keratoconjunctivitis, which are common culprits during this early phase.

This practice takes animal welfare into account, making it fundamental and necessary for the success of any productive system. Herd health plans must consider Clostridiosis and keratoconjunctivitis, which are common culprits during this early phase.

![]()

Besides vaccination, it is also essential to carry out adequate deworming during this period. Considering the fact that this intensive practice tends to increase the risk of gastrointestinal disease, and the developmental problems associated with it.

It is worth highlighting that claves subjected to early weaning practices will initially be a little more susceptible. Therefore, they require more attention at first.

If there are losses or reductions within the herd, the end goal is lost and the whole production cycle is compromised.

These practices are profitable if they are well planned and strategically used. It has already been demonstrated from a technical and nutritional standpoint they are applicable. However, it is worth remembering that the decision to adopt these strategies depends upon specific circumstances and economic scenarios.

| Feed, which accounts for the majority of total production costs, must be adjusted to the weight gain and development of calves. As well as in relation to the improvement of pregnancy rates in cows. |

CONCLUSIONS

Studies like the ones previously mentioned, help us to rethink alternatives that seek continuous improvement in livestock production systems.

This search for efficiency and improved performance is what maintains production systems. Therefore, as with any other breeding and handling methods, we must take care of animal welfare. Taking into account that this is a key factor that will influence the final result.

If these premises are met, results will most likely be profitable and satisfactory for producers.

You may like to review our previous entry: “Calf nutrition: weaning practices – Part I.”

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado