25 Aug 2022

25 Aug 2022

Dietary fat and its influence on rumen microbiota.

This second entry, analyzes the results obtained by researchers in the in vivo trials previously mentioned. As well as delving in fat biohydrogenation with greater depth. A process that follows after lipolysis once fats are within the rumen, as it was previously described in the first entry.

Detoxifying adaptation-biohydrogenation

This process is considered as a detoxifying adaptation (Kemp et al. , 1984), and marginally contributes to the elimination of reducing equivalents produced by rumen fermentation (Lourenço, et al. 2010).

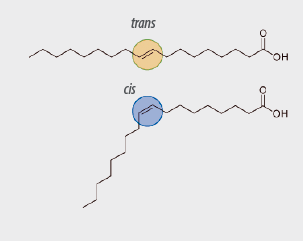

Biohydrogenation (BH) comprises several steps, depending on the USAFs, as well as several pathways, depending on diet and rumen environment (Griinari et al., 1998).

Protozoa encompass bacteria, and bacterial biohydrogenation can take place within protozoa (Jenkins et al., 2008) which explains their high concentrations of intermediate products (Devillard et al. , 2006).

In Vivo Studies

Beyond studies based on the selected isolates, in vivo trials have been carried out to evaluate the relationship between rumen bacteria and biohydrogenation. This has been done by adding bacteria and quantifying their products, or by adding dietary supplements known to affect BH and measuring bacterial abundance.

As a rule

Other observations ….

Observations on archaeal community

Methanobrevibacter ruminantium

Studies with pure strains of archaea adding organic acids or saturated fatty acids evidenced an inhibition of methane production by Methanobrevibacter ruminantium.

About linoleic acid ….

[register]

Altogether these early studies on saturated and monounsaturated FAs emphasize that the effects of fats on rumen bacteria depend on: bacterial metabolism, FA unsaturation, and the geometric configuration of double bonds.

The negative effects of FA on B. fibrisolvens are:

+ stronger for ALA than for LA

++strong for eicosapentaenoic long chain FA(EPA; cis-5, cis-8, cis-11, cis-14, cis-17-C20: 5 )and docosahexaenoic acids (DHA; cis-4, cis-7, cis-10, cis-13, cis-16, cis-19-C22: 6).

Similarly, ALA strongly increases the latency phase and decreases the growth rate of Propionibacterium acnesn (Maia et al., 2016).

Effects on bacteria in vivo

The effects of fat supplements were investigated in vivo, assigning bacteria to species level using quantitative PCR (Martin et al., 2016; Vargas-Bello-Perez, et al., 2016) or, at genre level, using 16S rDNA pyrosequencing (Zened et al., 2013a; Huws et al. , 2014).

In the latter, significant effects of fat were found in bacteria not yet cultured or not classified

These experiments were mainly based on the addition of oil, unlike most studies on pure strain cultures that used free FAs.

Overall, the effects were less than those observed with pure cultures. This could be due to the type of fat that was added or the fact that effects within the latency phase cannot be seen in vivo.

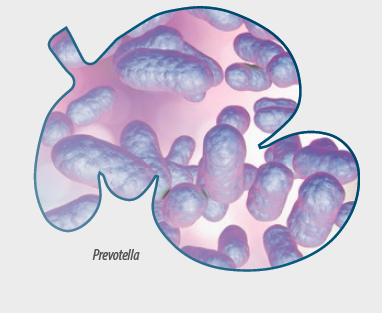

Changes in the rumen microbiota due to a higher concentrate proportion are much higher than the effects associated with addition of fats. It is also worth mentioning that some genera were affected differently by the addition of oil in low- and high-concentrate diets. This was especially true for Acetitomaculum, Lachnospira and Prevotella (Zened et al. 2011).

Among the genera of bacteria or species that were studied in several experiments, Fibrobacter and Ruminococcus were negatively affected in most cases, but the effects on Butyrivibio and Prevotella were highly variable.

The latter genera comprise many species with somewhat different functions, different metabolic pathways, and different sensitivities to FA in crops (Maia et al., 2007).

A decrease in the in vivo abundance of a bacterial genus after a change in diet cannot be unequivocally interpreted as a direct effect of a diet, but could reflect a more global change in nutrient degradation and in the relationships between different microorganisms in the rumen.

How do FAs inhibit bacterial growth?

There are several hypotheses to explain the inhibitory mechanism of GGs in bacterial growth:

Conclusions and perspectives

The relationship between dietary lipids and rumen microbiota is dominated by the toxicity of UFAs in many microorganisms, especially fibrolytic bacteria.

Many recent studies suggest that the biochemical pathways are more complex and that the bacteria involved could be more diverse than previously believed several decades ago.

Practical applications involve both sides of this relationship.

The most suitable options for shaping the rumen microbiota and its activity depend on many factors:

However, to apply these different manipulations in the field, new data must be obtained in vivo under various dietary conditions with long-term studies because the resilience of the rumen microbiota or its adaptation to the degradation of plant compounds can alter the effects over time (Weimer 2015).

In addition, conducting new applied research on rumen fat metabolism makes it necessary to better understand which microorganisms, which enzymatic mechanisms and which interactions between microorganisms and between the microbiota and the host are involved.

[/register]

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado