Hoof health, or foot health of pregnant sows, has become a reason for culling. This issue can account for 5–10% of culling within the breeding herd, which makes it necessary to analyze the causes in order to take appropriate measures.

Additionally, the culling of pregnant sows due to hoof or claw problems not only impacts ![]() meat production, but also increases operational costs because of the need to replace the removed animals.

meat production, but also increases operational costs because of the need to replace the removed animals.

It is therefore crucial to investigate and understand the underlying causes of these conditions. Among the potential solutions, adequate supplementation with specific minerals can play a key role in improving hoof health in pregnant sows, reducing culling rates, and optimizing overall reproductive herd productivity.

Hoof health and its relationship with nutrition

The hind hooves are usually the most affected. There are several conditions that can compromise the hoof health of sows, including:

![]() Sow weight

Sow weight

It is important to understand that gestation leads to a significant increase in the animal’s weight, which can be around 30 kg. The pressure from this additional weight falls directly on the sow’s hooves and/or phalanges, potentially compromising hoof health.

![]() Mobility

Mobility

When the animal is confined to a gestation crate, its mobility is significantly restricted. In this situation, natural hoof wear does not occur, leading to potential malformations. The lack of exercise also results in underdeveloped anatomical structures—such as muscles and cartilage—which compromises hoof health and structural strength.

![]() Mobilization of Body Reserves

Mobilization of Body Reserves

It is well known that a sow must mobilize her body reserves to support the development of the fetuses she is carrying. Lipid and protein tissues are broken down to supply the necessary nutrients for fetal growth and development. However, she also mobilizes minerals, which are essential for the bone development of her piglets.

Hoof injuries in sows lead to a decrease in feed intake, which can result in nutrient deficiencies in the animal. If this condition is not corrected, the performance in future farrowings may be negatively affected.

The hoof of a sow is primarily composed of keratin, a structural protein rich in cysteine, which forms disulfide bonds to provide strength. Collagen also plays a crucial role in the underlying dermis of the hoof, providing support and flexibility. It is classified into three types:

![]() Type 1: Predominates in the dermis of the hoof, providing strength and structure.

Type 1: Predominates in the dermis of the hoof, providing strength and structure.

![]() Type 2: Found in smaller amounts and contributes to the elasticity and regeneration of the tissue.

Type 2: Found in smaller amounts and contributes to the elasticity and regeneration of the tissue.

![]()

Type 3: Part of the basal membranes that support the epidermis of the hoof.

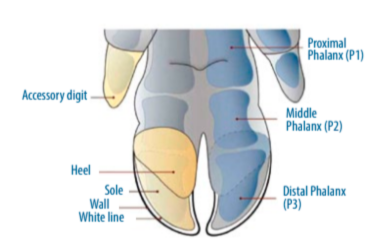

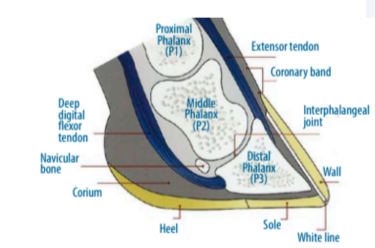

The following figures show the anatomical structure of pig hooves:

Figure 1. Posterior view of the hoof. Image courtesy of Zinpro Corporation, Guide for lesion classification.

Figure 2. Longitudinal section of a hoof – Image courtesy of Zinpro Corporation, Guide for lesion classification.

This figure shows the keratin coating around the phalanges. This structure is a thin covering that provides protection to the ligaments and phalanges.

Key minerals for hoof health

Zinc

Zinc is a trace mineral involved in more than 300 enzymatic reactions in a pig’s body, many of which are related to growth, healing, and the integrity of the skin and hoof. Some key functions of zinc in hoof quality include:

![]() Keratin synthesis: Zinc is a cofactor of keratinase, an enzyme that regulates keratin formation in the hoof. Its deficiency causes cracks, peeling, and fragile hooves.

Keratin synthesis: Zinc is a cofactor of keratinase, an enzyme that regulates keratin formation in the hoof. Its deficiency causes cracks, peeling, and fragile hooves.

![]() Disulfide bond formation: Keratin requires disulfide bonds for its strength. Zinc is involved in the activation of enzymes that stabilize these bonds.

Disulfide bond formation: Keratin requires disulfide bonds for its strength. Zinc is involved in the activation of enzymes that stabilize these bonds.

![]() Tissue regeneration:Adequate zinc supply improves cell proliferation and collagen synthesis, accelerating damage repair. In sows with hoof lesions, zinc helps reduce inflammation.

Tissue regeneration:Adequate zinc supply improves cell proliferation and collagen synthesis, accelerating damage repair. In sows with hoof lesions, zinc helps reduce inflammation.

Symptoms of zinc deficiency in sows include:

![]() Brittle hooves with cracks

Brittle hooves with cracks

![]() Parakeratosis

Parakeratosis

![]() Poor healing of wounds on the hooves

Poor healing of wounds on the hooves

![]() Recurrent lameness

Recurrent lameness

Copper

Copper is another essential mineral for hoof health, as it is involved in collagen formation and in the synthesis of disulfide bonds in keratin.

![]() Collagen and elastin synthesis:Copper activates lysyl oxidase, a key enzyme for the formation of type 1 collagen and elastin in the dermis of the hoof. Copper deficiency can weaken the hoof structure, making it more susceptible to lesions.

Collagen and elastin synthesis:Copper activates lysyl oxidase, a key enzyme for the formation of type 1 collagen and elastin in the dermis of the hoof. Copper deficiency can weaken the hoof structure, making it more susceptible to lesions.

![]() Formation of disulfide bonds in keratin: Copper stabilizes keratin, enhancing the hardness and strength of the hoof. Its deficiency can cause soft hooves that are prone to fractures.

Formation of disulfide bonds in keratin: Copper stabilizes keratin, enhancing the hardness and strength of the hoof. Its deficiency can cause soft hooves that are prone to fractures.

![]()

Antioxidant activity: Copper is a component of superoxide dismutase (SOD), an antioxidant enzyme that protects the hoof from oxidative damage and mechanical stress.

The signs of copper deficiency in sows are described as:

![]() Weak and brittle hooves

Weak and brittle hooves

![]()

Reduced hoof elasticity

![]()

Increased incidence of lameness and hoof deformities

Manganese

Manganese is a fundamental mineral for the formation of connective tissue and cartilage, which directly influences hoof quality. Some of its functions include:

![]() Synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans:Manganese is essential for the production of chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine, which strengthen the hoof and prevent deformities.

Synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans:Manganese is essential for the production of chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine, which strengthen the hoof and prevent deformities.

![]() Prevention of hoof lesions: A diet with optimal levels of manganese reduces the incidence of cracks and deformities in the hoof.

Prevention of hoof lesions: A diet with optimal levels of manganese reduces the incidence of cracks and deformities in the hoof.

![]() Antioxidant activity and bone metabolism:Manganese activates the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase enzyme, which protects the hoof from oxidative stress. This enzyme also participates in bone formation, helping to maintain structural stability.

Antioxidant activity and bone metabolism:Manganese activates the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase enzyme, which protects the hoof from oxidative stress. This enzyme also participates in bone formation, helping to maintain structural stability.

Symptoms of manganese deficiency:

![]() Deformed hooves or with longitudinal cracks

Deformed hooves or with longitudinal cracks

![]() Higher risk of arthritis and joint problems

Higher risk of arthritis and joint problems

![]() Difficulty healing hoof lesions

Difficulty healing hoof lesions

Hoof health not only depends on the minerals previously described. It is also closely related to other nutrients:

![]() Sulfur-containing amino acids (methionine and cysteine): These are essential for keratin synthesis. Deficiency can cause weakness in the hoof structure.

Sulfur-containing amino acids (methionine and cysteine): These are essential for keratin synthesis. Deficiency can cause weakness in the hoof structure.

![]() Biotin (vitamin B7): This nutrient improves keratin hardness and prevents cracks in the hoof. An intake of 10 mg/day of biotin is recommended to reduce hoof problems.

Biotin (vitamin B7): This nutrient improves keratin hardness and prevents cracks in the hoof. An intake of 10 mg/day of biotin is recommended to reduce hoof problems.

![]() Essential fatty acids (Omega-3 and Omega-6):They improve hoof elasticity and reduce inflammation in cases of hoof lesions.

Essential fatty acids (Omega-3 and Omega-6):They improve hoof elasticity and reduce inflammation in cases of hoof lesions.

![]() Vitamin A: Promotes regeneration of the hoof’s epithelial tissue. Its deficiency can cause defective keratinization.

Vitamin A: Promotes regeneration of the hoof’s epithelial tissue. Its deficiency can cause defective keratinization.

![]() Vitamin E and selenium: These antioxidants reduce oxidative stress and improve the health of connective tissue.

Vitamin E and selenium: These antioxidants reduce oxidative stress and improve the health of connective tissue.

Some nutrients included in the diet, such as minerals (Zinc, Copper, and Manganese), are essential for hoof quality in sows, as they are involved in the synthesis of keratin, collagen, and connective tissue.

An insufficient supply of these minerals can cause brittle hooves, cracks, and lameness, negatively impacting productive performance and animal welfare.