13 Jul 2022

13 Jul 2022

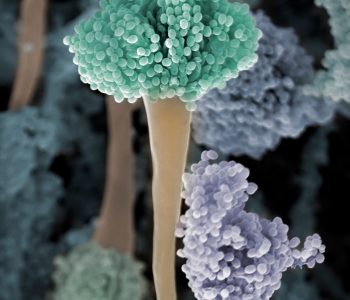

Ochratoxin A (OTA) is one of several fungal mycotoxins that have generated great public concern worldwide. The disease caused by exposure to OTA is known as ochratoxicosis, affecting the kidney as its target organ.

Ochratoxin A can be found in a large number of foods. The highest reported incidence of this mycotoxin was found in cereals, and considering the fact that mycotoxins can be transferred through the food chain, it can also be found in tissues and products of animal origin. Including pork, poultry and dairy products, among others (EFSA, 2004).

Ochratoxin A is a secondary toxic metabolite produced mainly by some strains of the species Aspergillus ochraceus and Penicillium verrucosum. These species can grow in different climates:

In general, the formation of OTA occurs mainly after harvest in insufficiently dry cereals and cereal products. Factors that influence mycotoxin production include:

While A. ochraceus grows better on oilseeds (peanuts and soybeans) than on cereal crops, P. verrucosum may develop better on wheat and corn.

The presence of OTA in animal feed varies from country to country. The highest amounts have been reported in northern Europe and North America (World Health Organisation, 2002).

Effects of OTA on Animal Health and Production

![]() [register]Food contaminated with OTA has its greatest economic impact on monogastric animals. Ruminants are more resistant than monogastrics to the toxicity of this mycotoxin.

[register]Food contaminated with OTA has its greatest economic impact on monogastric animals. Ruminants are more resistant than monogastrics to the toxicity of this mycotoxin.

![]()

Pigs are generally considered to be the most susceptible species to nephrotoxicity caused by Ochratoxin A. Nephropathy, without renal impairment, was observed in sows fed diets containing 1 mg OTA/kg feed for two years. On the other hand, sows fed diets containing 0.2 mg OTA/kg feed showed no nephropathy signs during the same period(EFSA, 2006).

In another study carried out with pigs, ingestion of feed containing 25 μg of OTA/kg decreased feed efficiency, daily weight gain and final body weight (Malagutti et al., 2005).

![]() The poultry industry is also affected by Ochratoxin A contamination. Turkeys, chickens and ducklings are susceptible to this toxin. Typical signs of avian ochratoxicosis are:

The poultry industry is also affected by Ochratoxin A contamination. Turkeys, chickens and ducklings are susceptible to this toxin. Typical signs of avian ochratoxicosis are:

![]() Numerous studies revealed that even exposure to low levels of OTA (0.5 mg/kg feed) altered yields. Including reductions in feed intake, growth rate and poor feed conversion efficiency (Wang et al., 2009).

Numerous studies revealed that even exposure to low levels of OTA (0.5 mg/kg feed) altered yields. Including reductions in feed intake, growth rate and poor feed conversion efficiency (Wang et al., 2009).

![]() A reduction in egg production and egg weight was recorded in laying hens when the animals received an OTA-contaminated diet at levels of 2 and 3 mg/kg (Verma et al., 2003).

A reduction in egg production and egg weight was recorded in laying hens when the animals received an OTA-contaminated diet at levels of 2 and 3 mg/kg (Verma et al., 2003).

The following signs have been observed:

in chickens fed a diet contaminated with 2mg of OTA/kg (Hoehler and Marquardt, 1996).

Presence of OTA in animal products

The presence of OTA in food products of animal origin can occur as a result of both direct fungal contamination of animal products or from indirect contamination through contaminated food. The latter is usually the main cause of mycotoxin contamination problems.

![]()

Little information is available on the rate of transfer of this toxin to the milk of dairy cows. In dairy sheep, the remainder was less than 1% (Boudra et al., 2005). It is believed that the concentration of OTA in human milk or other non-ruminant mammals may be higher than that of ruminants (Müller and Müller, 1998).

The presence of Ochratoxin A in human food products both from plant and animal origin has been recognized as a potential danger to human health globally.

The strongest associations were observed with plant-based foods and to a lesser extent, with animal-based foods.

Mitigating the effects of Ochratoxin A in the animal industry

Several different strategies have been employed to reduce the risk of Ochratoxin A entering the animal feed industry or its transfer into the food chain.

| The main strategies aim to control the growth of Ochratoxin A-producing fungi during the harvest and storage period. |

For this purpose, acids (such as propionate) are usually included in feed to prevent mold growth and mycotoxin production.

Rigorous risk management protocols in food factories to prevent contaminated grains from being incorporated in animal feed, mycotoxin elimination from raw materials through chemical and physical methods, or the administration of OTA contaminated diets to less susceptible animal species, all represent alternative strategies considered by the feed industry.

The formal establishment of risk management protocols to identify mycotoxin contaminated ingredients is considered mandatory for food safety assurance.

![]() However, mycotoxin analysis with the use of ELISA are not very sensitive. On the other hand, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is likely to improve control strategies used within the food milling industry.

However, mycotoxin analysis with the use of ELISA are not very sensitive. On the other hand, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is likely to improve control strategies used within the food milling industry.

As a precautionary measure, it is important to ensure a quality control of each batch to confirm the absence of caked products and/or corroded, broken or damaged grains by insects.

Many physical methods, including the application of high temperature or heat drying, have been carried out to detoxify Ochratoxin A. However, once it it released into food, this type of mycotoxin is very difficult to destroy.

![]()

In case Ochratoxin A poses a risk for a certain feed, several treatment methods have been tested to eliminate or reduce its harmful effects in animals. These include the use of specific adsorbing agents that block mycotoxins found in digestive contents or microorganisms which are capable of biotransforming mycotoxins into non-toxic metabolites. As well as the use of antioxidant compounds.

The use of adsorbents that bind to mycotoxin efficiently in the gastrointestinal tract, presents a promising and inexpensive approach to reduce the negative effects of OTA within the animal industry.

Conclusion

Food contamination by Ochratoxin A has sparked widespread public concern around the world. The main reasons arise from the fact that this mycotoxin is considered a nephrotoxic and carcinogenic agent, being the cause of several kidney diseases.

OTA is found mainly in cereals and oilseeds and to a lesser extent, in animal products. However, several strategies are being carried out in the animal feed industry to prevent or reduce food contamination by this toxin.

The most applicable method so far is the establishment of risk management protocols to identify and prevent the incorporation of contaminated ingredients within animal feed.

Current mitigation strategies include the use of binding agents designed to block the absorption of OTA from the gastrointestinal tract, or microorganisms and enzymes capable of biotransforming mycotoxins into non-toxic metabolites.

[/register]

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado