It is time to update the old system of feedstuff nutrient evaluation to achieve precision nutrition.

The primary method for describing the gross nutrient composition of feed ingredients and feeds has changed little since the US Food and Drug Administration adopted the “proximate analysis” method in 1888. As analytical chemistry advanced, the knowledge of feed composition improved, and separate requirements were determined for each new nutrient, mineral, vitamin, amino acid, and some essential fatty acids.

However, the proximate analysis has persisted for the feedstuff trade and for estimating the energetic contributions of feed ingredients.

Feed chemistry was in its’ infancy when the proximate analysis, or Weende Method, was conceived in the city of Weende, in the Hanover Kingdom, in the 1860’s. The true nature of proteins and the other constituents was unknown. Dividing feed ingredients into the crude albuminous material, or protein, ether extract, crude fiber, and ash fractions, was state of the art then. Whatever was left over was called the “nitrogen-free extract” despite not being an extract at all. It was supposed to represent soluble or available carbohydrates.

The proximate analysis method has some helpful features. For instance, the nitrogen-free extract is found by difference, so the analytical results always add up to 1,000.00 g/kg. In reality, there are no perfect methods for chemically defining feed ingredients. Using one technique or set of techniques for analyzing all ingredients should not be expected to give perfect answers every time.

Finding and understanding why the composition of ingredients does not sum to 1,000 g/kg should lead to a better understanding of just what is in all the different feed ingredients.

The difficulty in describing feed ingredients is due to the great variety of nutrients and other chemicals across and within plant and animal species.

The proteins in each ingredient have different amino acids. Consequently, the proteins’ nitrogen and energy contents are unique for each ingredient. Starch from different strains of even one crop type, like maize, will have different branching among their glucose units and different molecular weights and physical properties. For instance, dent corns are used for feed, while waxy corns are used to make corn starch for food and corn gluten feed for animals.

The same applies to oligosaccharides, non-starch polysaccharides, pectins, lignin, and hemicellulose. Only cellulose is free of branching glucose chains, but the fibers can be of different lengths in different species and cultivars.

Some of the main lessons learned since the Weende Method (Proximate, meaning close), analysis was introduced in 1864 include:

- Protein comprises amino acids, which contain different amounts of nitrogen. However, many other compounds, like nucleotides, resins, nitrates, nitrides, and phospholipids, also contain nitrogen.

- Plants contain amino acids as protein, free amino acids, and peptides. Animals can use all of them for protein synthesis. From the animal’s perspective, the sum is called “True Protein”.

- The choline in lecithin (phosphatidyl choline) and betaine can be converted into glycine for amino acid synthesis by animals.

- Ether extract contains neutral lipids like the triacyl glycerides but also waxes resins, chlorophyll, and some, but not all, of the phospholipids.

- Crude fiber contains unabsorbed plant cell wall components, including lignin, but not all undigested and unabsorbed material can be fermented in the animals’ hindgut (true fiber).

- True fiber is the sum of the non-starch polysaccharides (pectin, hemicellulose, andcellulose) and lignin.

- The oligosaccharides, with 3 to 12 sugar residues, are good animal energy sources and have prebiotic properties, altering the animal’s intestinal microflora.

- Pectins can be good sources of energy for animals through fermentation. They also have prebiotic activities and enhance immune responses.

- Depending on the method used to determine ash, some minerals may be volatilized, and ash residue may contain bound carbon, oxygen, and sulfur.

Advances in analytical chemistry are again making it possible to define feed ingredients further to advance nutritional science. An Australian Feed Ingredient Database (AFiD) has been developed (Moss, 2024). . It includes more detailed information on the carbohydrate contents of typical feed ingredients than earlier databases. The AFiD database includes information on several five and six-carbon sugars that are found in many feed ingredients for poultry and swine.

The Armidale Method of categorizing the chemicals in feed ingredients was first conceived as a teaching tool. It shows students how modern 21st-century chemical knowledge relates to 19th-century methods still in everyday use. Data from the AFiD database and Feedipedia.com were combined to create a new feed ingredient database based on the Armidale Method.

The Armidale Method has been proposed as a more relevant method to describe feed ingredients based on our understanding of modern knowledge of the actual chemical composition, and not just components that are soluble or insoluble in various solutions, like the Weende Method.

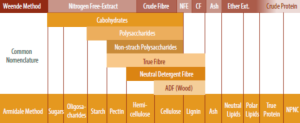

Table 1. Components of the Armidale Method of describing the composition of feed ingredients. From Pesti et al., 2024.

CP = Crude Protein, CF = Crude Fibre, EE = Ether Extract, NFE = Nitrogen-free Extract, Non-protein nitrogenous compounds

To categorize feed ingredient chemicals by the Armidale Method, the following measurements must be made:

- Sugars refers to the free sugars in an ingredient. They include mono and diglycerides like glucose, fructose, sucrose, xylose, and mannose.

- Oligosaccharides consist of sugar polymers of 3-12 residues.

- Starch refers to sugar polymers of more than 13 glucose residues.

- Lignin refers to polymers of phenolic residues. Therefore, they are not polysaccharides. Not only is lignin resistant to degradation, it is covalently bonded to cellulose and hemicellulose, which inhibits their degradation.

- Pectins are heteropolysaccharides found in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. Their primary units are sugar acids, mainly galacturonic acid. Pectins are soluble fibers that bind sugars and steroids in the gut and slow absorption and have immunomodulatory effects.

- Ash refers to the residue after burning the ingredient at 550 oC to remove all the carbon. It consists mainly of silica and other minerals.

- Neutral Lipids are compounds soluble in hexane, ether, and similar solvents. They include triacylglycerols, diacylglycerols, monoacylglycerols, free fatty acids, hydrocarbons such as waxes and steroids, chlorophyll, and pigments.

- Polar Lipids, including phospholipids, sphingolipids, and glycolipids, have limited solubility in hexane and ether and are better extracted in solvents like methanol.

- Cellulose, like starch, consists of polymers of glucose. Cellulose differs from starch in the type of linkage joining the glucose residues. Unlike starch, cellulose contains only linear chains of glucose.

- Hemicellulose refers to polymers that include 5-carbon sugars (like xylose and arabinose) and 6-carbon sugars (like mannose and galactose) and their sugar acids. Hemicellulose can contain branched chains of residues. There are four types of hemicelluloses found in different plants: xylans, mannans, mixed linkage beta-glucans, and xyloglucans.

- True Protein is the sum of all the amino acid residues in a feed ingredient. It can be thought of as representing the potential protein made from the feed ingredient. It does not distinguish between the amino acids in the ingredient that come from protein or peptide-linked amino acids and free amino acids. Methods to measure true protein in milk measure the peptide bonds, excluding any free amino acids.

- Non-Protein Nitrogenous Compounds include chemicals like DNA, RNA, phospholipids, betaine, nitrites, and nitrates. The choline in phospholipids is metabolized to betaine and then glycine. While phosphatidylcholine and betaine are not part of the true protein in feed ingredients, they can become parts of animal protein after ingestion due to their conversion to glycine.

- And Moisture.

Chemicals in the first eight categories are measured directly. Additional measurements that must be made are:

- Amino Acids in the ingredients are determined by standard methods.

- Nitrogen in the feed ingredient is determined by either the Kjeldahl or Dumas Combustion procedures.

- Neutral Detergent Fibre measures the total cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the cell walls of feed ingredients.

- Acid Detergent Fibre measures the cellulose and lignin in the cell walls of feed ingredients.

Then, the following calculations yield categories 9 – 12:

- Cellulose = ADF -Lignin

- Hemicellulose = NDF – ADF

- True Protein = Sum of the Amino Acid residues

- Non-Protein Nitrogenous Compounds = Crude Protein – True Protein

And:

Total Non-starch Polysaccharides (Total NSP) = Pectin + Cellulose + Hemicellulose

Total Polysaccharides = Starch + Total NSP

True Fibre is the sum of the Pectin, hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin.

There has been much conversation about “precision nutrition” and how it should be developed in the future.

However, it isn’t easy to make more precise feed formulas when they are based on the feed’s energy content, and this value is primarily based on 1860’s technology. A new system for describing feed ingredient composition is needed to make more precise feed formulas, especially ones with various proteases and carbohydrases.

The Armidale Method is a potential possibility. Much discussion amongst theoretical and practical nutritionists, analytical chemists, and statisticians is needed to refine and combine 160 years of advancements into a new system to facilitate further progress.

Figure 1. The composition of wheat using Weende (Proximate) Analysis (Left) and the Armidale Method (Right).

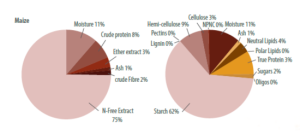

Figure 2. The composition of maize using Weende (Proximate) Analysis (Left) and the Armidale Method (Right).

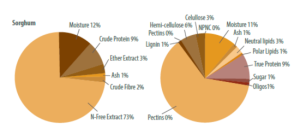

Figure 3. The composition of grain sorghum using Weende (Proximate) Analysis (Left) and the Armidale Method (Right).

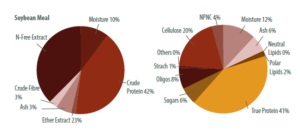

Figure 4. The composition of soybean meal using Weende (Proximate) Analysis (Left) and the Armidale Method (Right).

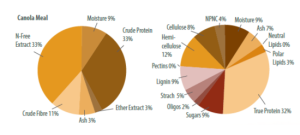

Figure 5. The composition of canola meal using Weende (Proximate) Analysis (Left) and the Armidale Method (Right).