30 Jun 2022

30 Jun 2022

Broiler production without the use of in-feed preventive antibiotics, has made gut health syndromes, diseases and associated performance losses rather common within the poultry industry. This has challenged producers and veterinarians to find solutions for maintaining production levels without the use of Antibiotic Growth Promoters (AGPS).

Broiler intestinal diseases and associated syndromes

Reductions or complete bans on antimicrobial use have resulted in the onset of diseases and syndromes that were previously overlooked or had low prevalence levels. Most of these syndromes are of intestinal origin and are associated with intestinal disturbances. Therefore, approximately 60% of therapeutic antibiotic use in broilers is related to intestinal disease control.

Reductions or complete bans on antimicrobial use have resulted in the onset of diseases and syndromes that were previously overlooked or had low prevalence levels. Most of these syndromes are of intestinal origin and are associated with intestinal disturbances. Therefore, approximately 60% of therapeutic antibiotic use in broilers is related to intestinal disease control.

Broilers often have gut barrier integrity issues (increased permeability) which makes it easier for toxins, feed antigens, bacteria and bacterial by-products to cross this barrier and spread systemically. This bacterial dissemination can also be a possible cause of osteoarticular disease. As bacteria which are disseminated systemically through the circulatory system can find colonize different sites within the body including bones. It is assumed that bacteria cross the intestinal barrier, enter the bloodstream and spread to osteochondritic clefts or to microfractures at the growth plates. When colonizing the growth plates, the bacteria are rather inaccessible to antibiotics and the host immune system, enabling them to induce necrosis. Causing osteoarticular compromise that adds to the great pressure put upon the skeletal system by the elevated body weight gain of broilers. As a result, lameness in broiler chickens is a significant animal welfare problem, with an elevated prevalence amongst productive flocks (up to 1% of all animals).

Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis (BCO) is a disease characterized by bacterial infection in rapidly growing bones under repeated mechanical stress and typically occurs in tibiae, femora and the thoracic vertebrae (Wideman, 2016).

Bacteria that are found in BCO lesions are commensal intestinal bacteria that have translocated through the intestinal epithelium and have spread systemically. Bacterial genera and species that are isolated from BCO cases are, amongst others, opportunistic bacteria including staphylococcus, Escherichia coli, and enterococci.

These kind of disease entities are thus again originating from high performance and at least partly have an intestinal origin. It has been shown that probiotics can affect BCO, again pointing to the intestine as origin of the bacteria that cause the disease (Wideman et al., 2015).

Measuring broiler intestinal health

Despite being a major research topic in many studies both in human and in veterinary medicine intestinal health is still a term that does not have a clear definition. This is partly so because it can be described at different levels. In the past, the use of different indirect systems such as measuring the water content of fecal material were used to make an approximation at assessing intestinal health. At a macroscopic level, optimal gut health can refer to a state where there are no noticeable changes in gut wall appearance when compared to normal conditions. While this is clear for conditions like necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis in which gross lesions are evident, this is not so clear or even undetectable for conditions causing microscopic alterations which affect performance.

Gut wall appearance: Evaluation methods

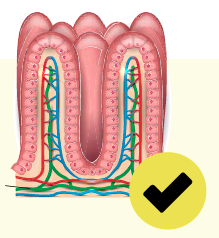

A scoring method for gut wall appearance was previously validated (Teirlynck et al., 2011) and many veterinarians employ it for broiler chickens. For this scoring system, 10 parameters are considered in total. These are assessed and given a score that ranges from: 0 when absent or 1 when present under visual inspection at necropsy of the intestinal wall. The animal receives a total score between 0 and 10 where, zero represents a normal gastrointestinal tract and 10 signals the most severe form of dysbiosis.

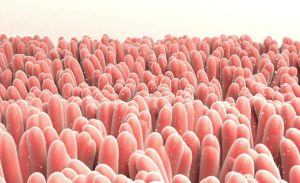

Therefore, a low score on gut wall appearance indicates good intestinal health. However, as this system depends on the perception of the observer carrying out the test it is considered rather subjective. As well as considering the fact that it is influenced by specific factors such as diet type (i.e. meal vs pellet) which will alter the potential presence of undigested feed particles at the time of examination. Nonetheless, it has been stated that the score of this type of evaluation correlates with histological parameters under certain conditions. Presenting a link that includes parameters like: villus length and immune cell infiltration of the gut wall (Teirlynck et al., 2011).

These parameters are considered to be more objective which allows to establish a clear correlation with gut health. This can be explained by the fact that they are markers for the state of the epithelial surface (villus length) and therefore have a direct association with digestibility and inflammation. Intestinal disruptions that alter the integrity of the epithelial lining and a result affect performance can be associated to this type of histological markers. However, although these parameters hold a certain value for evaluating gut health, their use is limited for experimental conditions. Due to the fact that they are useful under experimental interventions but their invasive and time-consuming nature makes them impractical in the field.

Finding accurate methods to assess gut health

Optimal gut health can be defined as a condition where there are no microscopically visible alterations. Other types of invasive biomarkers, can be found in the blood. Such is the case of acute phase proteins (APP) which are produced in the liver. Their production can be the result of intestinal inflammation caused by bacteria. This triggers cytokine production by epithelial and immune cells which are then sensed by liver cells, resulting in the production of APP.

Bacterial translocation through the gut wall allows these pathogens and their by products to reach the liver through the bloodstream. This can also generate a response in which hepatocytes secrete APP. APP levels can be measured in serum, but their production can be triggered anywhere in the animal’s body. Therefore it cannot be considered a specific biomarker to determine intestinal health(Langhorst et al., 2008; Eckersall and Bell, 2010).

Other biomarkers that could be potentially found in serum are of microbial origin. Increased intestinal permeability in poor gut health conditions can lead to translocation of bacteria, LPS and metabolites such as D-lactate, which can then be found in serum. However, these markers don’t seem to be very reliable according to various researchers.

Importance of Non-invasive biomarkers

Non-invasive markers are usually preferred on the field. Considering sampling complications this types of methods should be based on fecal material as it is easier to collect. Mixed faecal samples can be taken, which will allow to assess the gut health status of the whole flock. This type of markers can be microbial or host-derived. Microbial markers stem from the observation that gut health problems are usually associated with shifts in microbial composition.

While changes in microbial composition are clear in the case of severe intestinal inflammation, differences can be much more subtle in intestinal disorders with a much less clear phenotype. An example of this, is the irritable bowel syndrome in humans. The same is true for chickens, in which rather well-described microbial composition shifts have been described for the gut of animals with necrotic enteritis. However, despite numerous studies, it is not easy to identify biomarkers that clearly correlate with intestinal health and animal performance (Stanley et al., 2016).

Final Considerations

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado