04 Aug 2022

04 Aug 2022

Chromium: the final dietary adjustment in ruminants.

Cattle manage to express their genetic and reproductive potential when they meet their nutritional requirements.

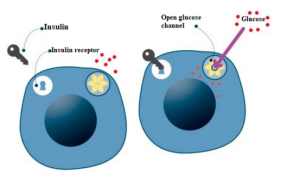

When the animal reaches high blood glucose concentrations, insulin is released. This hormone acts as “good news” by stimulating the animal’s body to face different scenarios such as adaptation to changes, immune activity or fertility.

However, cells may not respond properly to insulin stimulus, if they do not possess adequate amounts of a micromineral such as chromium (Cr).

Chromium can be found in feed, and if not, it must be supplemented. Within forages, the legume family is the one with the highest concentration (0.2 to 4 ppm DM) followed by grasses (0.1 to 0.35 ppm). While cereals contain much lower concentrations (0.01 to 0.55 ppm), amongst which corn is especially deficient (0.02 ppm-DM) (Lashkari et al. , 2018).

Chromium is only bioavailable to animals in the form of trivalent chromium (Cr+3), where it is associated with organic material. When this element enters the body as hexavalent chromium (Cr +6) it is not absorbed and can be useful as an inert indicator of dry matter consumption (Kim et al. , 2005).

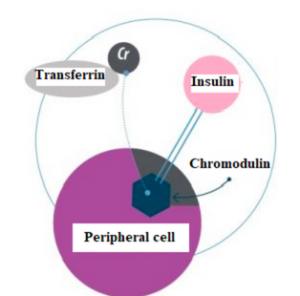

Cr is transported in the blood bound to transferrin and then taken by insulin-sensitive tissues, a hormone responsible for stimulating its uptake. When insulin binds to surface receptors on cells, Cr is taken up by a protein called chromodulin, which in turn stabilizes the hormone-receptor complex and facilitates its action by activating tyrosine kinase.

The moment insulin stops acting, Cr-bound chromodulin is released from the cell (Vincent, 2000). Endogenous Cr is eliminated especially in urine, while smaller amounts are eliminated through feces and milk (Bowen et al., 2009).

Chromium requirements

[register]Chromium requirements have not been clearly established (NRC, 2001; 2016). Such doubts are a result of the lack of knowledge regarding its metabolism. Being conditioned by tests with positive responses, which coincide with its use in animals under metabolic stress (McNamara and Valdés, 2005; Kafilzadeh et al., 2012).

Spears et al. (2012) observed a higher insulin sensitivity in Holstein heifers of 300Kg supplemented with Cr-propionate. In which a dose of 0.5mg/Kg DM of feed proved to be more effective than higher doses (1 or 1.5 mg/Kg DM of feed). On the other hand, when Cr-methionate was administered , a higher dose (0.8 mg/Kg) proved to be more effective than that of 0.4 mg/Kg in animals with the same weight (Kegley et al., 2000). Supplementation with Cr-methionine at 8mg total per day decreased heat stress in dairy cows in transition (Kafilzadeh et al. , 2012) or at 0.05 mg/Kg 0.75 (Mirzaei et al. , 2011).

Benefits of Chromium supplementation

The benefits of Cr supplementation could be summarized as an improvement in insulin functioning.

When animals are exposed to a negative energy balance, this metabolic state is expressed through a reduction in glycemia and a subsequent decrease in insulin levels.

Catabolic state maintenance or intensification results initially in limited production. However, if it is prolonged, vital functions such as immunity or fertility become compromised.

Thus, when the insulin response improves, extreme lipomobilization and the risk of ketosis and fatty liver onset decrease (Cook et al., 2001).

![]() The insulin response is more important when diets are rich in corn kernel than when supplemented with citrus pulp or protected fats (Leiva et al. , 2017 and 2018).

The insulin response is more important when diets are rich in corn kernel than when supplemented with citrus pulp or protected fats (Leiva et al. , 2017 and 2018).

Dairy cattle

![]()

In dairy farms, improvements where seen in: immune response within stressful situations, such as postpartum, as well as in reproductive indices. This was evidenced through:

Favorable fertility results were obtained in dairy cows under intensive grazing in New Zealand which were supplemented with Cr (6.25 mg/day). Decreasing plasma levels of NEFA (Non-Esterified Fatty Acids) (Bryan et al. , 2004).

Beef cattle

![]() In feedlot farms, supplementation with organic sources of Cr showed improvements in performance while reducing the incidence of bovine respiratory disease (BRD) in newly admitted calves (Moonsie-Shageer and Mowat, 1993; Chang et al., 1996).

In feedlot farms, supplementation with organic sources of Cr showed improvements in performance while reducing the incidence of bovine respiratory disease (BRD) in newly admitted calves (Moonsie-Shageer and Mowat, 1993; Chang et al., 1996).

Burton et al. (1994) observed that the supplementation of 6mg of Cr per animal produced an increase in the peak of neutralizing antibodies for infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus (IBR)after vaccination. This was no the case for Parainfluenza virus type 3 (PI 3) .

On the other hand, Wright et al. (1994) did not find differences in BRD morbidity. However, fewer antibiotic treatments were needed for disease control in animals receiving diets with 0.35 and 1.05 mg/Kg (DM) of Cr, compared to the non-supplemented group.

The method for determining Cr concentrations in tissues has improved in recent years. However, there are no reference levels through which an animal’s Cr status can be established. This conditions deficiency diagnosis to the positive responses to treatment (Suttle, 2010).

There are currently more studies evaluating the toxic effects than the therapeutic effects of Cr supplementation. This is because its use as a supplement in human medicine has become popular, where it is used as a dietary supplement to reduce weight and increase muscle development, becoming the second best seller after Calcium (Vincent, 2010).

In cattle, the doses used in supplementation are considered to be very far from the toxic ones, estimating a tolerance of up to 1000 ppm (DM) (NRC, 2005). However, there are studies that demonstrate the existence of optimal doses, after which efficacy in the response is lost.

●In this sense, Mirzaei et al. (2011) obtained improvements in:

at the beginning of lactation in Holstein cows subjected to caloric stress with 0.05mg of Cr (methionate)/Kg 0.75 of live weight, but the feed conversion was reduced when supplemented to double.

| In summary, positive results were achieved by supplementing adult animals with about 6mg daily of Cr in grazing systems (Bryan et al., 2004) or stables (Soltan, 2010) and 3 mg daily in growing animals (Spears et al. , 2012). |

Conclusions

Supplementation with trivalent chromium facilitates the action of insulin, this is what indicates that the animal is in a positive energy balance, therefore decreases the mobilization of adipose tissue and the risk of suffering ketosis and fatty liver in dairy cattle.

The reduction in lipomobilization generates lower concentrations of non-esterified fatty acids in the blood, thus also improving dry matter consumption and fertility.

On the other hand, chromium administration has been shown to improve:

– The immune system in both beef and dairy cattle

– The response of animals when subjected to caloric stress.

There is still a long way to go to determine the physiological requirements of chromium in livestock, as well as therapeutic doses.

[/register]

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado