30 Nov 2022

30 Nov 2022

Dietary inclusion of antibiotics for growth promotion in farm animal production has be a common practice for several decades. Resulting in increased efficiency levels in animal production.

Extensive research has been conducted over the past two decades to look for natural alternatives to antibiotics in feed. Plant compounds (or phytogenic compounds) have been attributed as great potential alternatives to AGPs (Yang et al., 2015).

![]() Amongst these, vegetable tannins have drawn considerable attention and are probably some of the most studied compounds. This is especially true for ruminants.

Amongst these, vegetable tannins have drawn considerable attention and are probably some of the most studied compounds. This is especially true for ruminants.

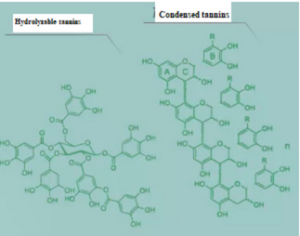

Chemical structure and presence of tannins

Tannins are a heterogeneous group of phenolic compounds with diverse structures that share their abilities to bind and precipitate proteins.

They are usually classified into 3 main groups:

The first 2 groups are found in terrestrial plants while PTs are found only in marine brown algae.

Tannins are widely distributed amongst the plant kingdom, being especially abundant in nutritionally important forages, shrubs, cereals and medicinal herbs (Salunkhe et al., 1982, Wang et al., 1999).

Tannins tend to be more abundant in the vulnerable parts of plants, e.g., new leaves and flowers (Terrill et al., 1992, Van Soest, 1982, Frutos et al. , 2004).

Chemical structures and tannin concentrations vary greatly between plant species, growth stages and growth conditions.

Biological activity of tannins

Tannins serve as part of the plant’s defense system against pathogen invasion and insect attacks. Thest possess numerous biological activities, such as:

These activities vary greatly depending on the chemical composition and structure of tannins. As well as due to other factors like: microorganism species, growth stages and/or host species (Hoste et al., 2006, Hoste et al. , 2012).

Use of tannins in ruminants

[register]Tannins, especially CTs, are widely distributed in nutritionally important forages, trees, and shrubs.

Condensed tannins may have beneficial or harmful effects for ruminants, depending on:

It is generally believed that the presence of CTs in tempered forages at low to medium concentrations (<50 g/kg DM) can benefits ruminant by improving protein utilization, without negatively affecting feed intake nor nutrient digestibility (Barry and Mcnabb, 1999, Waghorn, 2008).

Their capacity to precipitate proteins, as well as their antimicrobial, antiparasitic and antioxidant activities are probably the main reasons to consider the inclusion of tannins in ruminant diets.

Waghorn (2008)showed that when feeding forages as a single diet, an amount of approximately(30 g TC/kg DM) condensed tannins in L. corniculatus proved to be beneficial for ruminant production. On the other hand, CTs found in Hedysarum coronarium and L. pedunculatus ( with concentrations greater than 50 g/kg DM) did not seem to offer any other productivity benefit than mitigating parasite impacts.

Low to medium concentrations of condensed tannins can benefit the efficiency of ruminant production. As these reduce protein degradation within the rumen, which increases the amount of dietary protein that reaches the small intestine and is absorbed (Wang et al., 1994, Wang et al. , 1996). Low to medium concentrations of condensed tannins can benefit the efficiency of ruminant production. As these reduce protein degradation within the rumen, which increases the amount of dietary protein that reaches the small intestine and is absorbed (Wang et al., 1994, Wang et al. , 1996). |

![]() However, at high dietary concentrations, CTs affect feed intake due to their astringent nature. Reducing the digestion of proteins and other nutrients by over-protecting proteins, decreasing rumen microbial activity, and inhibiting the activity of endogenous digestive enzymes. All of these effects cause a significantly negative impact on animal performance.

However, at high dietary concentrations, CTs affect feed intake due to their astringent nature. Reducing the digestion of proteins and other nutrients by over-protecting proteins, decreasing rumen microbial activity, and inhibiting the activity of endogenous digestive enzymes. All of these effects cause a significantly negative impact on animal performance.

Probably the most successful application of dietary tannins in ruminant production is for the reduction of foamy tympanism. This condition is characterized by gas buildup within the rumen and reticulum, which affects both digestive and respiratory functions(Wang et al., 2012).

Many factors can contribute to the onset of tympanism. However, the rapid lysis of legume plant cells such as alfalfa and the release of proteins from plant cells within the rumen,are a major contributing factor. As they increase the viscosity of rumen fluid.

Li et al. (1996) have estimated that concentrations as low as 1.0 mg CT/g DM can prevent grass swelling.

Another important application for dietary tannin inclusion in ruminants, is the control of digestive parasites. This is especially true for grazing ruminants.

Another important application for dietary tannin inclusion in ruminants, is the control of digestive parasites. This is especially true for grazing ruminants.

Challenges of using tannins as an alternative to antibiotics in animal feed

The aforementioned information demonstrates that although plant tannins evidence strong antibacterial and antiparasitic action in vitro, their in vivo effects can vary significantly.

Many factors such as:

contribute to this great variability.

![]()

Due to the complexity of these issues, systematic and comprehensive evaluations on the efficacy and safety of these compounds are difficult. This scenario hinders the adoption of tannins and products containing tannins as viable alternatives to antimicrobial growth promoters within the animal production industry.

Most of the tannins which are currently used in the animal industry are crude extracts from mixtures of different molecular sizes or whole plants with a wide variety of secondary compounds.

However, little research has been done in this area up until now. Therefore, it is necessary that both the scientific community and the production industry make joint efforts to prevent microorganisms from developing resistance to tannins and other secondary plant compounds. As these represent important tools for human health, and the risk of new resistant microbial strains would have severe implications for humanity.

[/register]

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado