05 Dec 2022

05 Dec 2022

Acidifier inclusion in piglet diets represent a beneficial nutritional tool if used adequately.The intestinal health of the piglet is influenced by feed components. The content and composition of the fibrous fraction of the feed, the protein content and its origin, the influence of certain minerals, such as zinc and copper, and the presence of probiotics, prebiotics, enzymes and other nutraceutical additives can modify intestinal health and the subsequent development of the piglet.

Restrictions on antibiotic use, growth promoters and zinc oxide have made it necessary to invest in research to find solutions that increase or maintain productive results during a critical period of piglet development as weaning.

![]()

In order to achieve this, adequate diets are a key factor. Providing the necessary nutrients while helping to prevent common digestive disorders during this early life stage. There are different strategies and measures to be taken into account, ranging from the use of high quality ingredients to the inclusion of different additives or combinations of them.

Among the available additives, acidifiers (organic and inorganic acids) have been widely used in recent years due to their positive effects on piglets’ health. This is especially true at the intestinal level, which results in enhanced production efficiency.

Although there have been numerous studies evaluating different acidifiers, there is great variability regarding the responses to them (see meta-analysis of Tung and Pettigrew, 2006). This is not only true between different acids, but also in relation to the pig’s different growth stages. Due to differences between:

![]() Acids

Acids

![]() Dose

Dose

![]() Period of time through which they are administered.

Period of time through which they are administered.

![]() Diets

Diets

![]() Animal health

Animal health

![]() Rearing conditions

Rearing conditions

![]() Age of the pigs

Age of the pigs

MODE OF ACTION OF ACIDIFIERS

Different mechanisms have been proposed and validated to explain the action of acidifiers.

The reduction of stomach and intestinal pH promotes an increase in antimicrobial activity and a change in the stomach and intestinal microbiota, as well as an improvement in the digestibility, above all, of the protein fraction due to its effect on pepsin.

On the other hand, the metabolic effect of acids due to their energy intake cannot be ignored, as well as their contribution of other highly digestible nutrients if their salts are used.

DECREASED PH OF GASTROINTESTINAL CONTENTS

The gastric pH of the newly weaned piglet is higher (less acidic) than that of an adult pig. Therefore, any action taken to reduce it, in theory, will affect the microbiota of the stomach and/or the intestine.

The stomach pH of the piglet is usually ≥ 5 moments after weaning due to:

![]() Poor production of hydrochloric acid (HCl).

Poor production of hydrochloric acid (HCl).

![]() Lack of lactic acid due to lactose fermentation.

Lack of lactic acid due to lactose fermentation.

![]() A diet change, where there is a shift from ingesting small volumes of milk during lactation at infrequent intervals, to ingesting large amounts of solid food (Suiryanrayna and Ramana, 2015).

A diet change, where there is a shift from ingesting small volumes of milk during lactation at infrequent intervals, to ingesting large amounts of solid food (Suiryanrayna and Ramana, 2015).

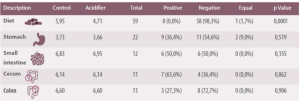

The acidification of diets decreases their pH from 3.73 to 3.66 (Table 1). However, available data does not suggest that there are pH reductions in gastrointestinal or stomach contents(Tung and Petigrew, 2006).

The acidification of diets decreases their pH from 3.73 to 3.66 (Table 1). However, available data does not suggest that there are pH reductions in gastrointestinal or stomach contents(Tung and Petigrew, 2006).

Authors pointed out that a reduction of stomach pH was seen in 55% of cases, being greater in 36% of cases, while in it remained the same 9% of cases. Hence, they concluded that dietary acidification has little influence on gastric pH.

Table 1. Summary of the effects of dietary acidifiers on intestinal content, an the pH values of: the stomach, small intestine, cecum and colon (Modified from Tung and Petigrew, 2006).

It seems that despite widespread belief, acids tend to increase the number of coliforms and E. Coli found in the stomach. On the other hand, these effects are highly variable in other parts of the intestinal tract.

The amount of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria is reduced in the small intestine (not statistically significant) and in the cecum.

In the colon, Lactobacillus and E. coli numbers are lower when formic acid or its calcium salt are included in the diet.

It is unclear whether this means that acids reduce the total number of bacteria in the large intestine. With results being more variable when other acids or their sodium salts were used.

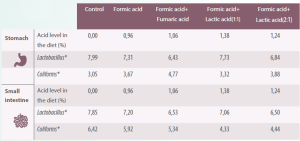

Table 2. Effect of organic acids on the microbiota in the stomach and small intestine of the piglet (Adapted from Franco et al., 2005).

*Log10 per gram or mL

Table 3. Effect of organic acids on the microbiota in the large intestine of the piglet (Adapted from Gedek et al., 1992).

*Log10 per gram or mL

Diets with a high buffer capacity possibly compromise the capacity of acid secretion in the stomach of piglets. Therefore, these will require the addition of considerable acidifier levels. These types of diets usually have high levels of proteins and minerals, especially calcium and fishmeal and products that provide vegetable protein.

One of the main problems in measuring the pH of stomach contents is that its highly heterogeneous. As well as due to the fact that they present different pH values in different parts of the stomach.

![]() This sometimes makes it difficult to compare different studies. However, it is assumed that, within a study, the techniques are the same and the data will have consistency.

This sometimes makes it difficult to compare different studies. However, it is assumed that, within a study, the techniques are the same and the data will have consistency.

The time that elapses between the last feed intake and the time of gastric pH measurement greatly influences the values recorded.

Interestingly, formic acid administered at 1.8% to weaned piglets kept gastric pH below 3 for several moments after feed intake.

However, when considering the mean of all sampling times of 0.5 to 8.5 h after intake, the gastric pH value was not affected by formic acid (Canibe et al., 2005). This result shows that high-dose formic acid may help counteract the buffering capacity of the diet, but at the same time, suggests that sampling time may often explain the different results between different studies.

MODIFICATION OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL MICROBIOTA

The low pH of the gastric contents is considered to kill or inhibit the growth of ingested bacteria.

The antimicrobial capacity of acidifiers is most important in undissociated forms of carboxylic acids which diffuse better across the cell membranes of microorganisms. They then dissociate within the cell’s cytoplasm, altering the osmotic and pH balance of microorganisms, as well as blocking enzyme and nutrient transport systems. This results in cellular death without membrane lysis although there can still be endotoxin release(González Mateos, 2007).

![]()

This is due to its lipophilic character and the relatively high pH inside bacterial cells. Which allows the acid to dissociate and break the cellular balance. This mechanism tends to be more effective in some bacteria than in others (Partanen, 2001) depending also on the type of acid, its dose and the diet.

![]()

The effects of acids and acidifiers on gastrointestinal microbiota can have have big variations depending on the GI section under study.

These inconsistent effects along the gastrointestinal tract are likely related to the lack of sufficient amounts of undissociated acids after the stomach, which affects the antimicrobial capacity of organic acids.

Organic acids

In fact, in many cases, dietary supplemented organic acids have only recovered in concentrations higher than the non-supplemental control in the stomach and proximal small intestine, subsequently disappearing into the contents of the distal small intestine and large intestine (Zentek et al., 2013).

MCFA

Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA), caprylic acid and, to a lesser extent, 0.3% capric acid, have shown to reduce E. coli counts in the jejunum and the cecum content of weaned piglets (Hanczakowska et al., 2016).

Organic acids + MCFA

Mixtures of organic acids and MCFAs have shown changing results. Which range from the reduction of E. coli and increased microbial diversity in the colon or showing no effects on fecal or large intestine microbiota at all (Li et al., 2018).

In summary, it could be said that acids tend to reduce the populations of Lactobacillus in the intestine and E. coli in the colon. Which supports the claim stating that these alter the microbiota of the digestive tract. However, the nature of such alteration still requires a validation methodology.

Can organic acids modify fermentation patterns or metabolite production?

Organic acids have the ability to modify fermentation patterns and ammonia production in the gut.

![]()

In vitro studies have demonstrated this ability, while in vivo studies the effects of dietary organic acids on fermentation patterns throughout the gut appear to be more variable.

According to Gabert and Sauer (1994), the use of formic acid at a dose of 0.3-3% does not alter the production of ammonia nor volatile fatty acids along the gastrointestinal tract.

However, in other studies, formic acid or its salts have been shown to increase the level of acetic acid, decreasing the concentration of lactic acid in the contents of the ileum, cecum and colon (Canibe et al., 2005).

These findings could indicate a change in gut microbiota composition and a modulation of microbial fermentation with more nutrients (glucose not fermented in lactic acid) or metabolites (such as acetate) made available for the piglet (Tugnoli et al., 2020).

METABOLIC EFFECTS OF ACIDIFIERS

The main metabolic effect of acids in piglets is that of being energy sources.

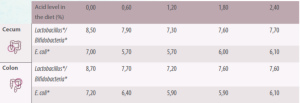

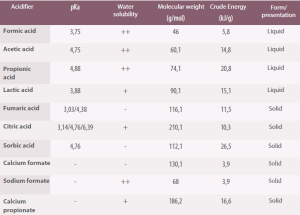

Table 4. Physical and chemical properties of the most commonly used organic acids as dietary acidifiers (Roth, 2000).

pK a = -Log10 ([H+] [A-]/[HA]). Solubility: ++/+/- high, medium, low.

Acids and their salts also provide other highly digestible nutrients to the diet, for example, calcium formate which, in addition, helps reduce calcium carbonate and has a buffering capacity. Other acids, such as butyric acid, are a source of energy for intestinal enterocytes.

Another metabolic effect of acids at the stomach level is that they are a source of chlorine. Which acts in the the activation of pepsinogen, and contributes to increasing protein digestibility.

PROTECTED ACIDS

In recent years, acid recoating or microencapsulation techniques have improved their functions within animals. As well as enabling a better practical handling, both at factory and farm level.

![]()

Microencapsulation improves palatability, which provides an opportunity to include higher acidifier doses while making it possible to reach the intestine if that is the intended action.

Generally, microencapsulation is performed with lipids that are digested in the duodenum. This effect can have good or bad consequences, depending on the objectives behind its addition:

![]() If the inclusion is aimed at lowering gastric pH, it will not be effective..

If the inclusion is aimed at lowering gastric pH, it will not be effective..

![]()

If the addition is aimed at reducing the number of coliforms, it could prove to be effective.

Microencapsulation also reduces the acidifier dose needed to achieve antibacterial effects (Piva et al., 2007).

Excessively high levels of acids in their pure form, which are more volatile than their salts can cause appetite issues. Thus, salts of the same acids tend to be less problematic. These will not have an effect on the pH of feed but, once ingested, they will dissociate and will have some effect on the gastrointestinal tract pH ( González Mateos, 2007).

The inclusion of acidifiers in piglet and pig diets, in general, consistently increases production results under practical rearing conditions.

![]()

However, there is a high variability in terms of reducing the pH of gastrointestinal content, increasing protein digestibility and modulating the microbiota. Exerting an important role in the piglet’s intestinal health.

In addition, acids play an important role in animal metabolism. Being butyric acid and medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) some of the most prominent ones.

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado