02 Jan 2024

02 Jan 2024

Taste System: A Key Component in Poultry Nutrition

|

|

This enables species to identify their counterparts, engage in reproductive activities or self-defense (social interactions), adapt to different ecosystems, and consume well-balanced diets, among other essential functions.

The sense of taste is primarily linked to the nutritional content of food, having evolved to recognize key elements in the diet like carbohydrates (sweet), amino acids (umami), organic acids (sour), minerals (salty), as well as toxins and other substances that may be difficult to digest or toxic (bitter), and potentially fats.

The sense of taste is primarily linked to the nutritional content of food, having evolved to recognize key elements in the diet like carbohydrates (sweet), amino acids (umami), organic acids (sour), minerals (salty), as well as toxins and other substances that may be difficult to digest or toxic (bitter), and potentially fats.

That is why this sense has garnered great attention among nutritionists.

Historically, birds have been undeservedly categorized as a discredited group of animals labeled “lacking taste” (frequently lacking smell as well). However, this perception is far from accurate.

| In this article, we will explain how birds (particularly the species of greatest commercial interest, Gallus gallus domesticus) not only possess high taste sensitivity but also use taste to detect nutritional deficiencies in diets and, therefore, adapt feeding behavior to achieve perfectly balanced diets. |

TASTE APPARATUS IN THE ORAL CAVITY OF BIRDS

TASTE APPARATUS IN THE ORAL CAVITY OF BIRDS

The taste apparatus in birds differs from that known in mammals, including humans. Firstly, the epithelium of the tongue in birds is covered with keratin, which does not provide suitable support for taste perception.

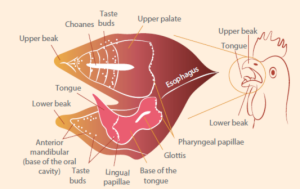

Unlike mammals, the avian tongue does not serve as a crucial sensory organ; its primary role is linked to gathering and swallowing food. Instead, the soft tissue of the palate, especially the upper palate, featuring localized salivary secretion, provides an ideal epithelium to accommodate the avian taste system (Figure 1) (Niknafs et al., 2023)..

Figure 1. Distribution of taste buds in the oral cavity of the chicken (published by Niknafs et al., 2023).

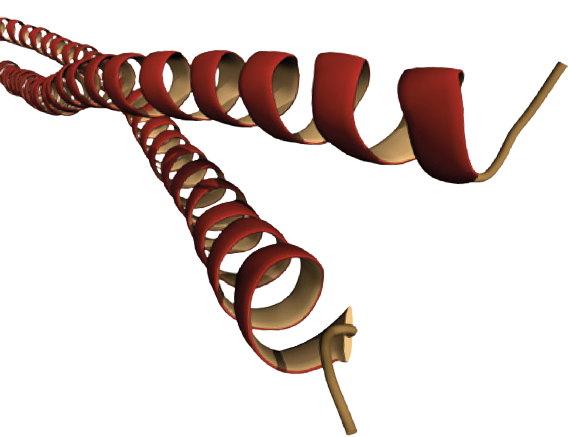

Figure 2. Basic structure of the taste bud: 1) Taste nerve fibers; 2) Synapse between nerve and sensory cell; 3) Type III gustatory sensory cell (or synaptic cell); 4) Basal cell; 5) Supporting cell; 6) Type II sensory cell; 7) Cellular microvilli; 8) External pore (to the surface of the palate); 9) Palate epithelial cell (drawing by Joaquim Roura).

| Secondly, taste in birds is not organized into papillae as in mammals but has evolved with the direct inclusion of taste buds among the rest of the epithelial cells (Figure 2). Taste buds are mainly located in the upper palate, sublingual area, and pharynx, forming “clusters” around salivary ducts (Kurosawa, 1983; Rajapaksha et al., 2016).. |

These pseudo-organs allow birds to perceive taste through taste receptors expressed in the sensory cells that make up this structure (Roura et al., 2013).

These pseudo-organs allow birds to perceive taste through taste receptors expressed in the sensory cells that make up this structure (Roura et al., 2013).

![]()

The Gallus species has an extraordinary taste capacity with 767 taste buds identified in the oral cavity, most of which are located in the upper palate (Rajapaksha et al., 2016).

![]() PERCEPTION & TASTE RECEPTORS

PERCEPTION & TASTE RECEPTORS

The sense of taste in chickens is crucial in influencing both the selection and quantity of feed consumed, directly impacting the growth of the bird.

![]() For this reason, in chickens, taste perception has been the subject of study with the aim of enhancing feed consumption and productivity. The taste qualities generated by nutrients and other components present in the diet have been inferred based on what is known in humans (for example, sweet and salty).

For this reason, in chickens, taste perception has been the subject of study with the aim of enhancing feed consumption and productivity. The taste qualities generated by nutrients and other components present in the diet have been inferred based on what is known in humans (for example, sweet and salty).

|

However, the advent of the genomics era has contributed to expanding knowledge about perception and molecular mechanisms, such as taste receptors in birds. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that taste receptors involved in nutrient detection are highly conserved in both birds and mammals (Roura et al., 2013, Niknafs et al., 2023). |

In short, the activation of transmembrane taste receptors (mostly from the GPCR family) initiates a cascade of intracellular reactions that lead to the activation (by membrane depolarization) of the taste cell, cranial nerve, and cerebral excitation in the primary taste-related area, thereby generating the sensation of taste.

In short, the activation of transmembrane taste receptors (mostly from the GPCR family) initiates a cascade of intracellular reactions that lead to the activation (by membrane depolarization) of the taste cell, cranial nerve, and cerebral excitation in the primary taste-related area, thereby generating the sensation of taste.

Table 1. Macronutrients associated with flavors

Specifically, taste receptors type 1 (T1R), whose ligands are sugars and amino acids, mediate what would be equivalent to the sweet and umami tastes in humans. Meanwhile, the bitter taste is mediated by the type 2 family of taste receptors (T2R).

Specifically, taste receptors type 1 (T1R), whose ligands are sugars and amino acids, mediate what would be equivalent to the sweet and umami tastes in humans. Meanwhile, the bitter taste is mediated by the type 2 family of taste receptors (T2R).

Genome studies of chickens have revealed the absence of the essential Tas1R2 gene in sweet taste perception in mammals (Lagerström et al., 2006; Shi & Zhang, 2006).

Recently, taste receptors have been found not only in the oral cavity but also in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) in chickens and other studied animal species.

![]() This link to the digestive system is recognized as the need to oversee the presence and assimilation of nutrients beyond the oral cavity.

This link to the digestive system is recognized as the need to oversee the presence and assimilation of nutrients beyond the oral cavity.

![]() THE GUT-BRAIN AXIS AND CHEMOSENSORY PERCEPTION OF NUTRIENTS

THE GUT-BRAIN AXIS AND CHEMOSENSORY PERCEPTION OF NUTRIENTS

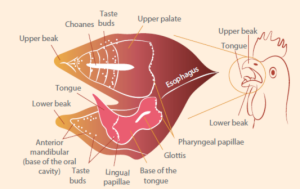

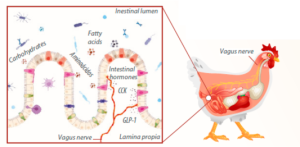

The taste receptors and nutrient sensors in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) respond to the food present in the lumen, which, in turn, triggers the secretion of intestinal hormones/peptides that affect appetite and satiety, such as Glucagon-like Peptide 1 (GLP1), cholecystokinin (CCK), or ghrelin.

Numerous functions have been attributed to taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), as previously described in association with enteroendocrine cells.

![]() These cells identify nutrients in the intestinal contents and produce signals that, via the vagus nerve, convey information to the brain.

These cells identify nutrients in the intestinal contents and produce signals that, via the vagus nerve, convey information to the brain.

It is important to note that endocrine cells constitute 1% of the cell population in the intestine.

In addition to vagal stimulation, intestinal peptides released into the extracellular space in the lamina propria can activate surrounding cells or travel through the circulatory or lymphatic system to other organs (Roura & Foster, 2018).

| These hormones are released as signaling molecules to convey information about the nutritional state to the brain (gut-brain axis) and |

Figure 3. Illustration of the gut-brain axis in chickens. Nutrients in the intestine activate enteroendocrine cells that secrete intestinal peptides, which, in turn, activate the vagus nerve, conveying the nutritional status of the chicken to the brain.

|

The discovery of the chemosensory nutrient system in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and the hypothalamus of birds, associated with the enteroendocrine system, has provided new tools with the potential to contribute to avian nutrition. |

You may also like to read: “Feeding Programs and Eggshell Traits in Slow-Growing Broilers”

References

Baldwin, M. W., Toda, Y., Nakagita, T., O’Connell, M. J., Klasing, K. C., Misaka, T., Edwards, S. V., & Liberles, S. D. (2014). Evolution of sweet taste perception in hummingbirds by transformation of the ancestral umami receptor. Science, 345(6199), 929-933. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255097

Lagerström, M. C., Hellström, A. R., Gloriam, D. E., Larsson, T. P., Schiöth, H. B., & Fredriksson, R. (2006). The G protein-coupled receptor subset of the chicken genome [Article]. PLoS Computational Biology, 2(6), 0493-0507. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020054

Niknafs, S., Navarro, M., Schneider, E. R., & Roura, E. (2023). The avian taste system [Review]. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, Article 1235377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1235377

Rajapaksha, P., Wang, Z., Venkatesan, N., Tehrani, K. F., Payne, J., Swetenburg, R. L., Kawabata, F., Tabata, S., Mortensen, L. J., Stice, S. L., Beckstead, R., & Liu, H.-X. (2016). Labeling and analysis of chicken taste buds using molecular markers in oral epithelial sheets. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 37247. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37247

Roura, E., Baldwin, M. W., & Klasing, K. C. (2013). The avian taste system: Potential implications in poultry nutrition. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 180(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2012.11.001

Roura, E., & Foster, S. R. (2018). Nutrient-Sensing Biology in Mammals and Birds. Annu Rev Anim Biosci, 6(1), 197-225. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-030117-014740

Shi, P., & Zhang, J. (2006). Contrasting modes of evolution between vertebrate sweet/umami receptor genes and bitter receptor genes [Article]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 23(2), 292-300. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msj028

Subscribe now to the technical magazine of animal nutrition

AUTHORS

Nutritional Interventions to Improve Fertility in Male Broiler Breeders

Edgar Oviedo

The Use of Organic Acids in Poultry: A Natural Path to Health and Productivity

M. Naeem

Synergistic Benefits of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry, Swine, and Cattle

Gustavo Adolfo Quintana-Ospina

Hybrid Rye Potential in Laying Hen Feed Rations

Gwendolyn Jones

A day in the life of phosphorus in pigs: Part I

Rafael Duran Giménez-Rico

Use of enzymes in diets for ruminants

Braulio de la Calle Campos

Minerals and Hoof Health in the Pregnant Sow

Juan Gabriel Espino

Impact of Oxidized Fats on Swine Reproduction and Offspring

Maria Alejandra Perez Alvarado