High levels of zinc oxide in the diet can alter the metabolism of trace minerals and may be detrimental to the health of weaned piglets.

Zinc oxide is commonly used as a growth promoter and an alternative to antibiotics to prevent post-weaning diarrhea.

Despite the NRC (2012) recommendation of 80-100 mg/kg of zinc for piglets weighing 7-25 kg, the swine industry worldwide uses levels of up to 3000 mg/kg of zinc in the first weeks after weaning (Dalto and Silva, 2020; Yang et al., 2021, Faccin, et al., 2023).

Despite the NRC (2012) recommendation of 80-100 mg/kg of zinc for piglets weighing 7-25 kg, the swine industry worldwide uses levels of up to 3000 mg/kg of zinc in the first weeks after weaning (Dalto and Silva, 2020; Yang et al., 2021, Faccin, et al., 2023).

These nutrients are essential in pig nutrition, but the use of high levels has been questioned due to environmental and public health issues (antimicrobial resistance), leading European countries to restrict the use of supra-nutritional doses of zinc in pig diets since 2022.

These nutrients are essential in pig nutrition, but the use of high levels has been questioned due to environmental and public health issues (antimicrobial resistance), leading European countries to restrict the use of supra-nutritional doses of zinc in pig diets since 2022.

| However, there is still limited knowledge about the interactions between zinc metabolism and that of other trace minerals in different organs, making it challenging to develop new nutritional strategies to replace high levels of zinc oxide without compromising piglet health. |

As an illustration, elevated dietary zinc levels have the potential to trigger anemia and lower tissue iron (Fe) concentrations in various species (Yanagisawa et al., 2009; Hachisuka et al., 2021). While the mechanisms governing this interplay between zinc and iron remain poorly elucidated, there are hints of indirect zinc-induced effects via alterations in copper metabolism (Jeng and Chen, 2022).

As an illustration, elevated dietary zinc levels have the potential to trigger anemia and lower tissue iron (Fe) concentrations in various species (Yanagisawa et al., 2009; Hachisuka et al., 2021). While the mechanisms governing this interplay between zinc and iron remain poorly elucidated, there are hints of indirect zinc-induced effects via alterations in copper metabolism (Jeng and Chen, 2022).

- In fact, copper deficiency negatively impacts iron utilization in swine.

In a recent investigation conducted in our laboratory (Galiot et al., 2018), it was demonstrated that piglets, which were fed 130 mg/kg of copper, experienced a decline in both serum and hepatic copper levels (a reduction of 20% and 76%, respectively) two weeks after weaning. It was postulated that this decline in copper status was initiated by the elevated levels of zinc oxide in the post-weaning diet.

In a recent investigation conducted in our laboratory (Galiot et al., 2018), it was demonstrated that piglets, which were fed 130 mg/kg of copper, experienced a decline in both serum and hepatic copper levels (a reduction of 20% and 76%, respectively) two weeks after weaning. It was postulated that this decline in copper status was initiated by the elevated levels of zinc oxide in the post-weaning diet.

Hence, two studies were conducted to better understand the biological consequences of increasing dietary levels of zinc oxide and different zinc/copper ratios in the diet on the regulation of trace minerals (Zn, Cu, and Fe) in weaned piglets. [register]

Hence, two studies were conducted to better understand the biological consequences of increasing dietary levels of zinc oxide and different zinc/copper ratios in the diet on the regulation of trace minerals (Zn, Cu, and Fe) in weaned piglets. [register]

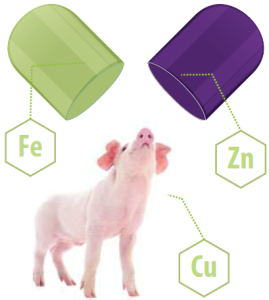

- Study 1: Basal diet supplemented with 100, 1000, or 3000 mg/kg of Zn (LZn, MZn, and HZn, respectively) in the form of zinc oxide. All three diets had similar copper levels (130 mg/kg; CuSO4).

- Study 2: dieta basal suplementada com 100 (LZn) ou 3000 (HZn) mg/kg de Zn na forma de óxido de zinco em combinação com 6 (LCu) ou 130 (HCu) mg/kg de cobre na forma de sulfato de cobre.

| The piglets were slaughtered on days 21, 23 (study 1), 28 (study 2), 35, and 42 for the collection of blood serum and body tissues. |

Growth performance

The use of supra-nutritional levels of zinc oxide in post-weaning diets is known to promote growth performance, although some studies did not detect beneficial effects (Espinosa et al., 2020ab).

The use of supra-nutritional levels of zinc oxide in post-weaning diets is known to promote growth performance, although some studies did not detect beneficial effects (Espinosa et al., 2020ab).

In our two studies, high levels of zinc oxide in the diet impaired growth.

- Specifically in study 2, the combination of high levels of zinc oxide and copper sulfate (HZnHCu) resulted in the worst performance, while beneficial effects of high levels of copper sulfate were observed only when low levels of zinc oxide were used.

The optimized environmental conditions (experimental setting) in these studies may have interfered with the primarily local effects (intestinal lumen) of zinc oxide.

Under these conditions, it is possible that the negative effects of high zinc oxide levels on metabolism prevailed over its positive effects observed in more challenging environments (high pathogenic pressure).

Under these conditions, it is possible that the negative effects of high zinc oxide levels on metabolism prevailed over its positive effects observed in more challenging environments (high pathogenic pressure).

| As for copper sulfate, a compound primarily known for its systemic effects, the experimental setting’s impact might have been comparatively less disruptive. |

Zinc

Intestinal zinc absorption is inversely proportional to its intake (Cousins, 1985; Krebs, 2000).

Intestinal zinc absorption is inversely proportional to its intake (Cousins, 1985; Krebs, 2000).

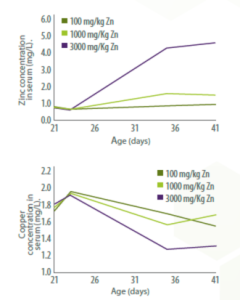

In both research studies, despite the fact that elevated zinc oxide levels decreased the expression of genes associated with the absorption of zinc in the intestine, there was no corresponding decrease in zinc concentrations in the jejunum, liver, and serum (as illustrated in Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Zinc (A) and copper (B) concentrations in blood serum.

Figure 2. Zinc concentrations in the jejunal mucosa (A) and liver (B).

In order to avert zinc levels reaching toxic thresholds, distinct cellular mechanisms were initiated in the jejunum and liver, with the purposes of (1) capturing zinc within cells and (2) discharging surplus zinc into the systemic circulation. In order to avert zinc levels reaching toxic thresholds, distinct cellular mechanisms were initiated in the jejunum and liver, with the purposes of (1) capturing zinc within cells and (2) discharging surplus zinc into the systemic circulation. |

Despite the activation of these mechanisms, serum and hepatic zinc concentrations increased significantly.

![]() In study 1, the 10-fold difference in zinc oxide levels in the diet between LZn and MZn resulted in an approximately 2-fold increase in serum levels, indicating zinc concentration modulation.

In study 1, the 10-fold difference in zinc oxide levels in the diet between LZn and MZn resulted in an approximately 2-fold increase in serum levels, indicating zinc concentration modulation.

- However, the 3-fold difference in zinc oxide levels in the diet between MZn and HZn resulted in a proportional increase in serum zinc levels, suggesting that regulation mechanisms were no longer efficient in controlling zinc excess in animals supplemented with HZn.

Across the two studies, serum zinc concentrations ranged from 4.1 to 4.6 mg/L on day 42 in piglets supplemented with HZn.

These serum zinc levels are known to be detrimental to pig performance (Hahn and Baker, 1993), supporting the reduced growth performance observed in our studies.

These serum zinc levels are known to be detrimental to pig performance (Hahn and Baker, 1993), supporting the reduced growth performance observed in our studies.

In study 2, hepatic zinc concentrations in the LZn groups on days 28, 35, and 42 represented 71%, 58%, and 66% of pre-treatment values (day 21), while serum values remained constant throughout the experimental period.

In study 2, hepatic zinc concentrations in the LZn groups on days 28, 35, and 42 represented 71%, 58%, and 66% of pre-treatment values (day 21), while serum values remained constant throughout the experimental period.

| These findings imply that a diet containing 100 mg of zinc oxide per kilogram during the initial weeks after weaning might not adequately fulfill the nutritional needs of piglets. |

Copper

Similar to zinc, copper absorption and bioavailability are inversely proportional to its intake (Jondreville et al., 2002; Dalto et al., 2019).

Similar to zinc, copper absorption and bioavailability are inversely proportional to its intake (Jondreville et al., 2002; Dalto et al., 2019).

- Regardless of the copper levels in the diet (130 ppm in study 1 and 6 or 130 ppm in study 2), piglets supplemented with HZn had higher copper concentrations in the jejunum compared to piglets in the LZn group (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Copper concentrations in the jejunal mucosa (A) and liver (B).

This increase was accompanied by lower hepatic and serum copper levels in the HZn group (Figure 1 and 3), suggesting a reduction in copper release by enterocytes.

This inhibition of copper efflux by intestinal cells is related to the activation of a mechanism responsible for mineral sequestration in different organs.

This process is regulated by an enzyme known as metallothionein (MT), which is sensitive to dietary zinc levels but exhibits a significantly greater affinity for copper.

This process is regulated by an enzyme known as metallothionein (MT), which is sensitive to dietary zinc levels but exhibits a significantly greater affinity for copper.

![]() In study 1, this enzyme showed a 357-fold increase in expression in the jejunum of HZn piglets compared to LZn piglets three weeks after weaning.

In study 1, this enzyme showed a 357-fold increase in expression in the jejunum of HZn piglets compared to LZn piglets three weeks after weaning.

Considering the rapid turnover of intestinal tissue (25% per day), this retention of copper in intestinal cells can act as a mechanism for copper excretion, as it serves as temporary storage for this mineral that is eventually lost through shedding of intestinal tissue.

Considering the rapid turnover of intestinal tissue (25% per day), this retention of copper in intestinal cells can act as a mechanism for copper excretion, as it serves as temporary storage for this mineral that is eventually lost through shedding of intestinal tissue.

Interestingly, in study 2, hepatic copper concentrations were lower than the pre-treatment values (day 21) from day 28 onwards, not only for the HZn groups but also for the LCu groups (Figure 3), while serum values were lower for all treatments. This indicates that 6 mg of Cu/kg of diet (LCu, study 2) would not be sufficient to meet the copper requirements of piglets in the early weeks post-weaning.

Interestingly, in study 2, hepatic copper concentrations were lower than the pre-treatment values (day 21) from day 28 onwards, not only for the HZn groups but also for the LCu groups (Figure 3), while serum values were lower for all treatments. This indicates that 6 mg of Cu/kg of diet (LCu, study 2) would not be sufficient to meet the copper requirements of piglets in the early weeks post-weaning.

Iron

High dietary levels of zinc oxide also disrupt iron metabolism through systemic (hepcidin) and local (intestine and liver) mechanisms.

- In both studies, piglets supplemented with HZn experienced a decrease in intestinal iron absorption, accompanied by an apparent increase in its retention in enterocytes, resulting in a reduction in hepatic iron content.

The limited storage of iron in the liver might have been worsened by an amplified release of this mineral by hepatocytes, which was also prompted by elevated levels of zinc in the diet.

The limited storage of iron in the liver might have been worsened by an amplified release of this mineral by hepatocytes, which was also prompted by elevated levels of zinc in the diet.

Nevertheless, these effects were not of sufficient magnitude to influence the overall blood and serum iron levels, as well as the concentrations of hemoglobin, all of which showed an increase over time in both research studies.

![]() Therefore, high levels of zinc oxide in post-weaning diets may not cause iron deficiency in piglets, but they hinder hepatic iron storage, which can be problematic in weaned animals with low iron reserves, as has been observed in recent years.

Therefore, high levels of zinc oxide in post-weaning diets may not cause iron deficiency in piglets, but they hinder hepatic iron storage, which can be problematic in weaned animals with low iron reserves, as has been observed in recent years.

This final aspect holds paramount significance, as variations in iron metabolism observed across our two studies indicate that pre-weaning factors could exert a substantial influence on the metabolism of this trace mineral during the post-weaning period, underscoring the need for further research.

This final aspect holds paramount significance, as variations in iron metabolism observed across our two studies indicate that pre-weaning factors could exert a substantial influence on the metabolism of this trace mineral during the post-weaning period, underscoring the need for further research.

Conclusions

During the first weeks after weaning, 100 mg of zinc/kg of diet appears to be insufficient to meet the zinc requirements of piglets.

Conversely, elevated levels of zinc oxide in the diet are inadequately controlled across various organs, leading to exceedingly high serum zinc concentrations. This is likely the cause of the decline in piglet performance and the disturbance of copper and iron metabolism.

Conversely, elevated levels of zinc oxide in the diet are inadequately controlled across various organs, leading to exceedingly high serum zinc concentrations. This is likely the cause of the decline in piglet performance and the disturbance of copper and iron metabolism.

Regarding iron, the reduced hepatic content did not have any impact on blood, serum, and hemoglobin concentrations, indicating that despite the interference with liver iron storage, the high levels of zinc oxide in post-weaning diets are unlikely to cause anemia in piglets.

A low zinc-to-copper ratio in the diet is advisable to safeguard the health of weaned piglets.

A low zinc-to-copper ratio in the diet is advisable to safeguard the health of weaned piglets.

| The low hepatic and serum copper concentrations underscore the potential risk of copper deficiency in piglets supplemented with high levels of zinc oxide in the post-weaning period. |

However, regardless of these significant zinc-related effects, supplementing with 6 mg of copper per kilogram of diet appears to fall short of meeting the copper nutritional requirements of these animals.

References available upon request. [/register]

This article was originally published as content in portuguese in nutriNews Brasil 2023